CHEAT SHEET

- Proportionality. Discovery must be proportional to the case needs, meaning the court and parties should consider the importance of the information, the level of difficulty it takes to produce, and whether the proposed discovery burden or cost outweighs its benefit.

- Arguing your case. In order to prove that the discovery is not proportional to the case, you must undertake the discovery you wish to avoid and present examples and cost calculations of the burden.

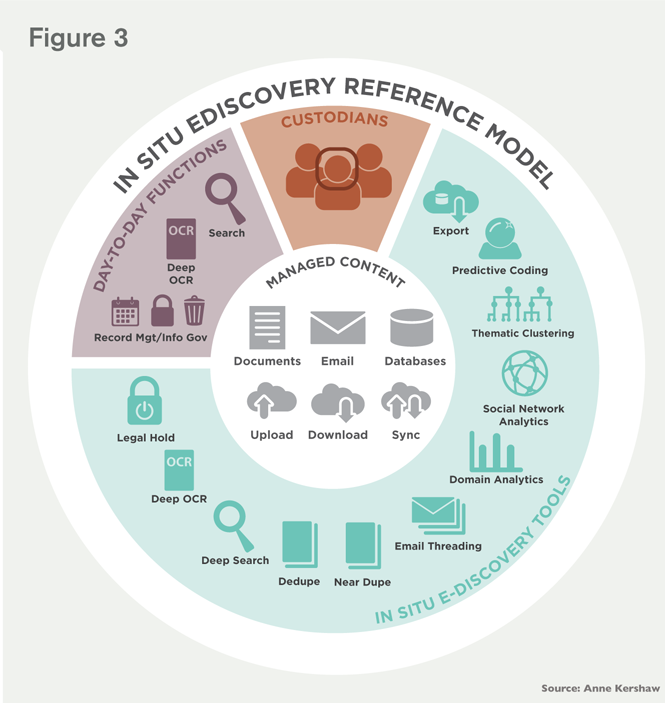

- In situ. New eDiscovery tools, like the in situ (in place) model can quickly and inexpensively gather the metrics needed to win proportionality arguments by allowing counsel to identify and analyze data sources.

- Five steps. Follow these steps to substantiate proportionality arguments: identify custodians; assess and rank custodian relevance; assess data sources; implement in situ eDiscovery tools; and build a strategy.

With the evolution of technology, documents have proliferated, moving from the file cabinet to the clouds. When litigation occurs, searching these vast troves of data can be overwhelming. The concept of proportionality in litigation requires discovery to be proportional to the needs of the case, and compels the court and the parties to consider how important the information is, how difficult it will be to produce, and whether the burden or expense of the proposed discovery outweighs its likely benefit. The courts and litigating parties share the responsibility to employ proportionality to curtail overzealous eDiscovery practices. Thanks to new tools, in-house counsel can quickly and inexpensively retrieve the necessary metrics and win arguments pertaining to proportionality in discovery.

Under the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, as well as most state civil litigation rules, proportionality is mandated. This makes sense. Parties in litigation shouldn’t have to do more discovery than is necessary to meet the needs of the case. Indeed, without proportionality, the door is opened for litigants to use discovery as a weapon to increase costs and force settlements in cases that have little or no merit. Historically, however, proportionality arguments have been difficult, if not impossible, to win.

It has been a chicken and egg problem — in order to obtain the metrics to show the other side is overreaching, in-house counsel needed to do the very discovery that the company wanted to avoid in the first place. Simply, it is impossible to convince a judge or adversary that what is being asked for is unnecessary if you are unable to demonstrate why. To do that, documents, or at least examples, and cost calculations associated with finding them, were necessary.

It has been a chicken and egg problem — in order to obtain the metrics to show the other side is overreaching, in-house counsel needed to do the very discovery that the company wanted to avoid in the first place.

Finally, there is an answer to this long-standing conundrum. The hypothetical case below shows how new tools for assessing relevant custodians and data sources, along with the use of in situ (in place) eDiscovery tools, can lead to a successful outcome. This workflow can quickly and inexpensively gather the metrics necessary to win proportionality arguments. Moreover, this workflow is particularly economical if lawyers for litigants are proficient in using the workflow and skilled in all aspects of proportionality decisions, including explaining the decisions during meet and confer negotiations, and defending the decisions in court. This article refers to lawyers with such skills as “proportionality counsel.”

Scrupulous litigators do not believe that their only obligation during discovery is to “give them what they ask for,” regardless of how extraneous the adversary’s requests may be. But, in some cases, concessions are made to engage in overbroad keyword searches, with the knowledge that such searches will be littered with false positive results.

While this approach may feel safe (“Your Honor, it’s what they asked for”), in truth it is a trap — no matter what is produced, an adversary will be able to raise questions as to completeness and the viability of the process used (“How do we know what they have not produced, your Honor? How can we know what is missing?”). It is a trap because, for the adversary with a weak case looking for a quick settlement, whatever is produced will never be enough. The producing party loses control of the discussion. While it cuts against the instincts of traditional defense litigation tactics, it is a far better strategy to show one’s cards, just a bit, to gain control of the discussion, and make the case for proportionality through solid research and assessment, as described below.

Hypothetical

A class action case has been filed against Red Circle Corporation (RCC) in the Eastern District of Virginia’s (EDVA) “rocket docket,” known for its speedy resolutions. The rocket docket has several unique local rules, but one thing is for certain: proportionality and speed are critical. The plaintiffs allege that RCC has been distributing and marketing defective widgets to the class of plaintiffs for years, dating back to around 2013. Among the allegations contained in the complaint is that RCC repeatedly misrepresented the durability of its widgets in marketing and promotional materials and relied on outdated testing principles to achieve its durability ratings. RCC has seen exponential growth over the years and has grown to over 5,000 employees across its engineering, marketing, sales, and product development departments in the United States alone.

The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (FRCP) require that a Rule 26(f) Meet and Confer conference be held “as soon as practicable,” and local EDVA rules shorten the timeline for this conference to be held in fewer than the 21 days allowed under the FRCP prior to the Rule 16(b) scheduling conference. Additionally, initial disclosures and discovery plans must be filed fewer than 14 days after the Rule 26(f) conference. Finally, EDVA rules require that discovery be completed within 90 to 120 days after the Rule 16(b) scheduling conference. EDVA strictly enforces these timelines, which can be daunting. Certainly, both FRCP and EDVA require practitioners to proactively apply proportionality and be prepared to act quickly. Time to move beyond the chicken and the egg conundrum.

Initial case assessment workflow

The wheel in Figure 1 provides an overview of the process that RCC’s legal department and proportionality counsel (or, for smaller companies, an eDiscovery consultant or lawyer) intend to follow in order to quickly and efficiently comply with the guidelines set forth by the FRCP and EDVA’s rocket docket. Each step is recorded in proportionality assessment software. The proportionality counsel reviews and analyzes the information and then makes and presents the proportionality assessments, defending his or her assessments to an adversary or judge. Such thorough documentation and review provide a concrete argument against overreaching discovery requests.

Case strategy

RCC was served with the complaint on April 15, 2020. Their initial disclosure obligation includes identification of relevant custodians, along with a description by category and location of all documents, both within and outside of their possession, that may be used to support its claims or defenses. In addition, RCC will need to anticipate the subject matter and categories of documents that plaintiffs will be requesting, as well as who will be deposed. Considering the allegations in the complaint, plaintiffs will seek discovery of all documents concerning documents relating to RCC’s marketing representations as to durability.

Preparing for the Rule 26(f) Meet and Confer/Initial disclosures

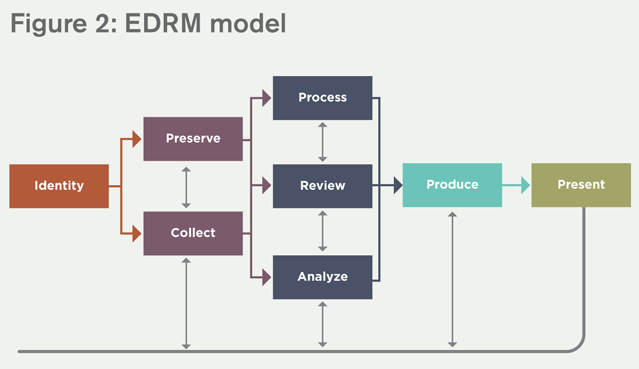

The five steps in Figure 2 provide a defensible and quantifiable method to substantiate proportionality arguments and lower the costs related to eDiscovery by utilizing technology and in situ methods.

Step 1: Custodian identification

Historically, a broad legal hold net is cast at this preliminary stage; a net that rarely contemplates whether individual custodians and data sources can be evaluated and released. In this case, however, the legal team adopts a proportionality mindset early, thereby creating a framework that identifies people and data sources that are most relevant to the claims and defenses at issue.

In this example, RCC engages proportionality counsel, who expeditiously compiles a preliminary list containing 113 potentially relevant custodians. These custodians are identified by speaking to senior managers and executives who were involved in widget testing and marketing. A legal hold notice is immediately issued to these custodians to inform them of their obligation to retain relevant documents and data, with the understanding that “compliance with [the] legal hold should be regularly monitored.”

After issuing a legal hold or preservation notice to any RCC employee who might have or know of relevant documents, the task for proportionality counsel is to:

- Identify who has, or knows where to find, documents regarding the testing and marketing of widget durability (the custodians); and

- Which of the document sources identified by the custodians contain relevant documents, and what are the best search criteria and filters for finding them.

Thankfully, due to the adoption of cloud services, most organizations can now conduct in situ eDiscovery, and it is no longer necessary to employ a full-blown, expensive, traditional eDiscovery process (the EDRM model in Figure 2) to accomplish task (b) above.

Step 2: Assess and rank custodian relevance

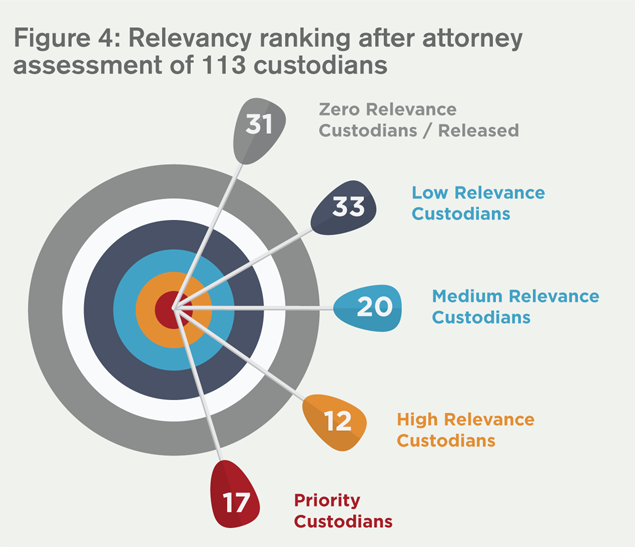

Understanding how each custodian’s position at RCC relates to the claims and defenses, and ranking them according to their relevancy, is the first step to quickly preparing to meet the expedited discovery requirements. To do this, proportionality counsel consults with RCC to construct six relevancy questions to determine which employees have knowledge about, and/or know of documents about, the testing and marketing of RCC’s widgets. Each question is assigned a score according to importance. Collectively, the number of affirmative responses creates an overall relevancy ranking for each custodian on a scale of high priority to low priority. Proportionality counsel completes a quick interview with each custodian to further determine and assess the relevancy ranking.

The preliminary relevancy score is used to determine which employees should be interviewed in more detail. Attorney involvement here is critical. They will vet custodian responses and the corresponding relevancy ranking. A technology-enabled approach is most expeditious for this purpose.

After the assessment interviews are completed, the following observations are made:

In this matter, 31 identified custodians were deemed to have no relevance to the matter. They were immediately released from the hold, instantly reducing the potential discovery burden for RCC.

Based on this preliminary assessment, the focus shifts to custodians identified as priority and high relevancy. This targeted approach is now focused on 26 percent or 29 of the 113 employees initially identified to potentially have relevant information. Significantly, proportionality counsel can now analyze and defend the decision to move forward with a particular set of custodians.

Important factors to remember when making proportionality arguments: An interview with Judge Christopher P. Yates

WHAT ARE THE MOST IMPORTANT THINGS TO REMEMBER WHEN APPLYING PROPORTIONALITY TO CASES?

Proportionality can manifest itself in at least two different ways in cases. First of all, at the outset of the case, when the attorneys and the judge are planning a case management order, it’s important to lay out the parameters of permissible discovery in a general sense to take into consideration the broad notion of proportionality.

And then, in the context of particular discovery disputes, it’s worth raising proportionality as a defense to discovery requests that are effectively overbroad in the context of the case. I’ve always said that the point of discovery isn’t to treat discovery as an end in itself, it’s merely a means to an end. And proportionality, I think, captures that notion by making clear that the appropriate amount of discovery is that which allows the parties to prepare themselves for a trial rather than that which answers every question anyone could ever have about the case.

SO, WOULD YOU AGREE THAT DISCOVERY SHOULD BE REASONABLE AND NOT EXHAUSTIVE?

Right. There is always a point in discovery where you’re arriving at diminishing returns. In other words, you can spend a million dollars to get the answer to every single question that anybody could ever have about the background of the case, but it’s just not worth it in 99 percent of the cases that get litigated. And so, it never makes sense to exhaustively discover a case. It always amuses me that civil litigators place such a premium on comprehensive discovery.

HOW IMPORTANT IS THE EARLY USE OF PROPORTIONALITY IN COMPLYING WITH THE CHANGES IN BOTH FEDERAL AND STATE LAWS THAT ARE INTENDED TO DRAMATICALLY SPEED UP THE DISCOVERY PROCESS?

One of the aims of innovations like mandatory initial disclosures is to force the parties to put the cards on the table earlier. This should, at least in theory, dramatically reduce the scope of necessary discovery. In other words, you don’t have to embark upon a protracted discovery process when both sides have to disclose 50 or 60 or 70 percent of their case at the outset of discovery. And so, I think the two fit together like a hand in a glove.

WHAT IS THE MOST IMPORTANT THING AN ATTORNEY SHOULD DO WHEN PRESENTING A PROPORTIONALITY ARGUMENT?

In the context of a particular motion, such as a response to a motion to compel discovery, the argument that the cost of the discovery and the time consumption of the discovery is just far beyond the needs of the case will always strike me as a persuasive argument. So, in order to effectively argue proportionality, you have to first put the discovery dispute in the broader context of the case and what it will look like when it goes to trial. And then, you also have to think about whether it makes sense from a financial standpoint to embark upon discovery that somebody is seeking to compel.

WHAT ARE THE SPECIFIC THINGS THAT AN ATTORNEY NEEDS TO DEMONSTRATE WHEN ARGUING THAT THE SCOPE OF DISCOVERY IS TOO DIFFICULT OR IS DISPROPORTIONATE?

One of the helpful innovations in the current Michigan Court Rules that I was involved in drafting, is that new rules take into account the fact that the cost of discovery should not always be imposed on the party that has to make the disclosures. And so, under the new Michigan rules, for example, there’s essentially a process available by which you can obtain electronic discovery of virtually everything as long as you’re willing to pay for it.

So, that essentially requires attorneys to think about whether it is, in fact, cost-effective, rather than simply making a broad demand and then insisting that the other side be forced to comply with the demand.

Often the response to any sort of discovery is to say that it is too expensive or logistically impossible or not worth the yield. And if I’m faced with that in the context of a dispute about electronic discovery, it is often my practice to appoint a technology expert under Michigan Court Rules 2.401(J) or the Federal Analog Federal Rule of Evidence 706. And for a relatively modest sum, that expert reports primarily to me rather than to one party or the other and can tell me in a demystifying way whether this sort of discovery is, in fact, unduly burdensome or unnecessarily expensive. So, I don’t just rely on my own knowledge and instincts. I rely on others as well.

IS IT HELPFUL TO THE COURT WHEN AN ATTORNEY CAN PRESENT A QUANTIFIABLE PROPORTIONALITY ARGUMENT?

It is. One of the great frustrations I have about conferences on discovery is that attorneys often come in and provide me with information that’s essentially useless to me. They’ll say, we’ve already turned over 67,000 documents. That’s an utterly meaningless statement, because if you simply took a page out of your college yearbook and ran it off 67,000 times and sent it to the other side, that’s not helping anybody. Discovery often is more about finding the needles in the haystack rather than just trying to increase the size of the haystack.

DO YOU HAVE ANYTHING ELSE TO ADD THAT YOU WOULD WANT CORPORATE COUNSEL TO KNOW ABOUT MAKING PROPORTIONALITY ARGUMENTS?

Yes. I’ve attended annual meetings of the American College of Business Court Judges for years. One of the best sessions we ever had was an afternoon session with two panels: the first consisting of general counsel from large corporations, and the second consisting of general counsel from medium-sized corporations. They told us that they were tremendously frustrated by the time and expense of discovery, and they told us that their attorneys always say the judges insist upon this much discovery.

Well, if I could be so bold as to speak directly to corporate counsel, I don’t know any judge who requires the assigned attorneys litigating the case to engage in excessive discovery. And so, if you think that the idea begins with the bench, it doesn’t. I would encourage corporate counsel to ask the difficult questions of their litigating counsel and try to figure out exactly who established the discovery schedule. I think it would even be helpful from time to time to go to some of those initial meetings with the judges where the schedule is worked out, because I always invite clients if they wish to come to attend those meetings. I think it’s important for everybody to have a say in the discovery schedule, and it’s especially important to have the people who are writing the checks to pay for the litigation to participate.

To comply with an expedited time schedule, assessing the scope of the matter quickly and efficiently is critical. In formulating their case strategy, the case team meets to assess the case parameters and potential exposure. RCC is concerned that public perception of their alleged guilt could be damaging to the company image. It is essential to pivot towards early disclosure and rapid resolution. Plaintiff’s counsel is known for filing nuisance class action claims and will use discovery to drive up costs to force a settlement. The monetary exposure is estimated between US$3-5 million.

Strategically, it is decided that early disclosure and transparency is the best approach as a counterbalance to excessive discovery. The FRCP and the EDVA’s rocket docket are structured to encourage counsel to focus on discovery on the merits instead of discovery about discovery, a characteristic that the expedited timeline supports. RCC believes that plaintiffs’ claims are unwarranted and can be easily disproved. If RCC can demonstrate this early and quickly, it can maneuver toward a quick resolution, thus reducing discovery expenditures and litigation costs significantly.

Judge Christopher P. Yates

17th Circuit Court Judge - Specialized Business Docket

Judge Christopher P. Yates was appointed to Michigan’s 17th Circuit Court on April 22, 2008, serving first in both the civil/criminal and family divisions. On March 1, 2012, he was assigned to the specialized business docket for the court. Judge Yates received a BA from Kalamazoo College in 1983, and a JD and MBA from the University of Illinois in 1987. As an attorney, Judge Yates served as a law clerk to Chief Judge James P. Churchill of the US District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan and to Judge Ralph B. Guy, Jr., of the US Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit. Judge Yates also has worked as an Assistant US Attorney in Detroit, an attorney-advisor in the Office of Legal Counsel at the US Department of Justice, as the Chief Federal Public Defender for the Western District of Michigan, and as a partner in two private law firms.

Step 3: Data source assessment

The next step in applying early proportionality is to assess data sources to identify relevant, unique data that relates to the specific claims and defenses of the matter. To do this, RCC’s proportionality counsel sends each custodian in the priority and high relevancy rankings an electronically distributed data usage survey. The survey asks where relevant data sources and locations may exist. This includes devices that are within the custodian’s possession or control, such as computers, phones, paper, and removable media, as well as non-custodial data sources, such as corporate devices and centralized sources such as email, business applications, and network shares. These surveys may also ask for information about potential custodians who may need to be added to the legal hold.

Once surveys are completed and collated, proportionality counsel conducts secondary interviews with the 29 custodians. These do not need to be lengthy interviews; rather, it allows proportionality counsel to clarify custodian responses to survey questions, personally speak to each custodian, and finally, to get a full understanding and assessment of the various data sources involved. Most importantly, proportionality counsel can pinpoint data sources containing unique and relevant data and identify those that are unnecessary for collection and review. All of this work is recorded in the proportionality software for discussion, presentation, and — if necessary — argument.

Equally important is providing an assessment of the difficulty of collection (and thereby cost) of each type of data source. Each data source is scored on the burden associated with collecting it (due to various technical aspects such as difficulties in making the data usable in a discovery sense). Proportionality counsel will use this information to make further proportionality assessments and arguments to avoid collecting burdensome sources. Thus, each data source is scored from low effort to highly burdensome.

Step 4: Using in situ eDiscovery tools to prove proportionality

Once the relevant custodians and data sources are identified, in situ eDiscovery tools allow proportionality counsel to analyze the data sources to determine which search parameters and filters will retrieve relevant documents most efficiently and which will not.

In this hypothetical, RCC had moved all of its electronic information systems to a cloud server in 2019 (think Enterprise Office 365 or Google Doc). This technology enables indexing in place without the necessity of moving the data outside the corporate firewall. The technology also provides a robust interface for in-depth search, retrieval, and assessment by proportionality counsel, as well as reporting features.

Using these in situ eDiscovery tools, proportionality counsel can now quickly find the documents concerning RCC’s testing and marketing of its widgets and rank these documents in terms of significance and by date, to determine who did what, and when. Indeed, this early assessment is used to generate a high-level chronology of meetings, decisions, and events. Proportionality counsel will also analyze communication patterns of custodians to identify normal channels of communication, as well as new or unexpected channels if necessary (i.e., confirm that there are no other employees with significant involvement relating to the matter that have not yet been identified).

This early data assessment is not intended to be exhaustive; rather, it is intended to provide a broad review of what the data represents. Using in situ eDiscovery tools provides immediate access to search, narrow, and target data based on both metadata and full text of the document corpus. A subset of documents determined to be highly relevant — and very helpful to RCC’s defense, if not dispositive — will be produced to plaintiff’s counsel as part of RCC’s initial disclosures under Fed. R. Civ. P 26(a)(1). The targeted search process can then be honed and refined throughout the negotiation process. Such early disclosures are pivotal to RCC’s strategy of knocking out plaintiffs’ superfluous claims before the expenditure of significant legal fees.

Step 5: Building a proportional discovery strategy

As shown by this hypothetical, understanding how to leverage proportionality assessments early offers a myriad of use cases and opportunities to streamline the overall discovery process and make it more transparent for both in-house and outside counsel. As such, a technology-enabled work-flow workflow, facilitated by attorneys who understand and can speak to the decisioning involved, provides a roadmap to operationalize proportionality. It provides counsel with quantifiable, transparent, and actionable intelligence to make informed decisions, based on information, not speculation.

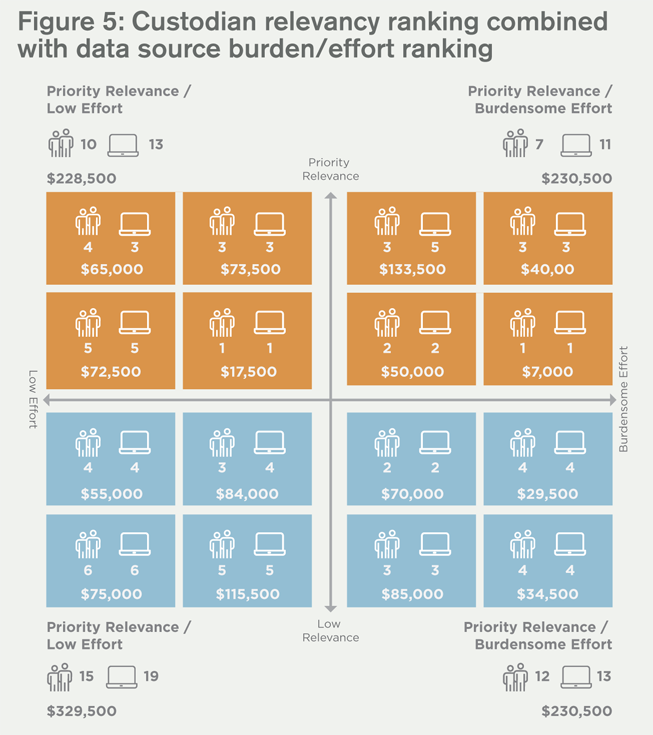

The chart in Figure 5 provides a roll-up of both the custodian relevancy ranking combined with the data source burden/effort ranking and is an excellent visualization for use in Rule 26(f) negotiations or in connection with discovery motions:

The “High Priority Custodians/Low Effort” classification in the upper left quadrant pinpoints the priority group to review and assess. Isolating this group early and focusing on disclosure and production of certain custodians and data sources in this quadrant provides a win-win for both parties because the approach results in early calibration of the most relevant custodians and their data. Further data analytics can also be performed within each quadrant to inform future negotiations.

The upper right quadrant includes data sources that are ranked as relevant but highly burdensome. As such, proportionality counsel performs an assessment to determine how unique the data is and whether the same information could possibly be located elsewhere. For data that is deemed to be unique, the difficulty and cost of moving the data through discovery is weighed against the amount in controversy, along with the degree of relevance to the issues in the case.

Using in situ eDiscovery tools provides immediate access to search, narrow, and target data based on both metadata and full text of the document corpus.

Certain data sources in this quadrant may be moved forward, but negotiation around sampling or cost shifting will be leveraged to mitigate the burden for the producing party.

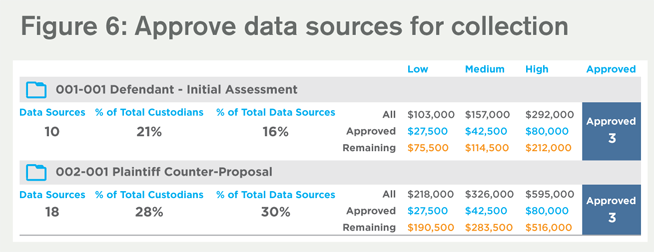

The two lower quadrants in blue represent the low priority custodian groups. From a negotiation perspective, RCC’s counsel opts to negotiate that moving this data forward is disproportionate to the needs of the case and will not lead to the discovery of valuable information. A sampling of data in these categories has been captured by proportionality counsel to demonstrate that unique, relevant content does not exist in the documents associated with these custodians. As demonstrated in the chart below, negotiation scenarios that provide real-time cost estimates will also be generated to represent the burden of moving these unnecessary custodians and data sources through the discovery process from collection through review and production.

Conclusion

By employing proportionality software throughout the process, proportionality counsel can provide the necessary metrics and reporting needed to support a defensible discovery approach. Reports are generated for all custodians organized by their relevancy ranking, with a subclassification of their data sources (plotted on a level of difficulty scale). This report is used by proportionality counsel as a cornerstone for negotiations and forms the foundation of a roadmap for prioritization of custodians and the corresponding preservation and collection activities. This framework can be memorialized as part of the parties’ stipulation regarding the scope and process for eDiscovery, the ESI Protocol.

At a minimum, opposing counsel will see that RCC is armed and ready to fight for proportionality in court, with proportionality counsel ready to attest about the research done and the decisions made. All of the research and decisions will be backed up with visualizations generated by the proportionality software throughout the process. Together, this framework facilitates making a powerful case that a new era of eDiscovery has arrived and in-house counsel would be wise to consider it. Technological advances and innovative thinking can solidify proportionality as a legal principle and change the overall approach to discovery, disarming those who attempt to brandish overbroad discovery requests as a weapon.

NOTES

1. Fed. R. Civ. P 26(b), titled “Discovery Scope and Limits,” provides in section (1): Scope in General. Unless otherwise limited by court order, the scope of discovery is as follows: Parties may obtain discovery regarding any nonprivileged matter that is relevant to any party’s claim or defense and proportional to the needs of the case, considering the importance of the issues at stake in the action, the amount in controversy, the parties’ relative access to relevant information, the parties’ resources, the importance of the discovery in resolving the issues, and whether the burden or expense of the proposed discovery outweighs its likely benefit. Information within this scope of discovery need not be admissible in evidence to be discoverable.

2. See e.g., In re Broiler Chicken Antitrust Litig., 2018 WL 3586183, at *4 (N.D. Ill. July 26, 2018) (“Apparently [Agri Stats] has not fully analyzed the cost impact of EUCPs’ revised search terms or narrowed document and data categories); Guerrero v. Wharton, 2017 WL 7314240, at *4 (D. Nev. Mar. 30, 2017) (“Defendant asserts without elaboration or factual support that producing the documents would cause him an “undue burden”); and Salazar v. McDonald’s Corp., 2016 WL 736213, at *4 (N.D. Cal. Feb. 25, 2016) (“The Court appreciates that discovery is often costly, but Defendant has not put forward an adequate argument about why discovery should be delayed,” citing Goes Int’l, 2016 WL 427369, at *4.)

3. It does not go unnoticed that the mounds of non-responsive documents, retrieved by using untested keyword searches, will substantially increase the expense of litigation due to legal fees incurred for the unnecessary document law firm review of irrelevant documents.

4. Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(f)(1).

5. Fed R. Civ. P. 16(b).

6. Fed R. Civ. P. 26(a)(1)(C).

7. E.D. Va. Civ. Rule 16(B).

8. Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(a).

9. The Sedona Conference, Commentary on Legal Holds, Second Edition: The Trigger & the Process, Guideline 10.

10. See Cache La Poudre Feeds, LLC v. Land O’Lakes, 244 F.R.D. 614, 628 (D. Colo. 2007) (discussing a company’s obligation to “undertake a reasonable investigation to identify and preserve relevant materials”). As denoted by the Sedona Commentary on Legal Holds, a “duty to preserve documents or other evidence arises when there is a reasonable anticipation of litigation.” Such preservation involves “reasonable and good-faith efforts, taken as soon as is practicable and applied proportionately, to identify persons likely to have information relevant to the claims and defenses in the matter.” The Sedona Conference, Commentary on Legal Holds, Second Edition: The Trigger & the Process.

ACC EXTRAS ON… eDiscovery

ACC Docket

In Situ eDiscovery Tools (Jan. 2020).

Bringing eDiscovery Home: The New In Situ Reference Model (Jan. 2020).

It’s Time to Bring eDiscovery In-house (May 2019).