Many companies worked to address the environmental, social, and governance (ESG) challenges that presented themselves last year: developing a post-COVID working model, improving diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI), and enhancing cybersecurity governance.

We promptly confronted risks that had previously been perceived as distant threats (global pandemic was low on that list). This is part of why investor shareholders are encouraging companies to improve environmental stewardship. It leaves many in-house legal and corporate responsibility teams with the daunting task of founding an environmental program while navigating other ESG priorities. Below are tips for successfully navigating the challenge.

Hurdles to getting started

Indirect causality

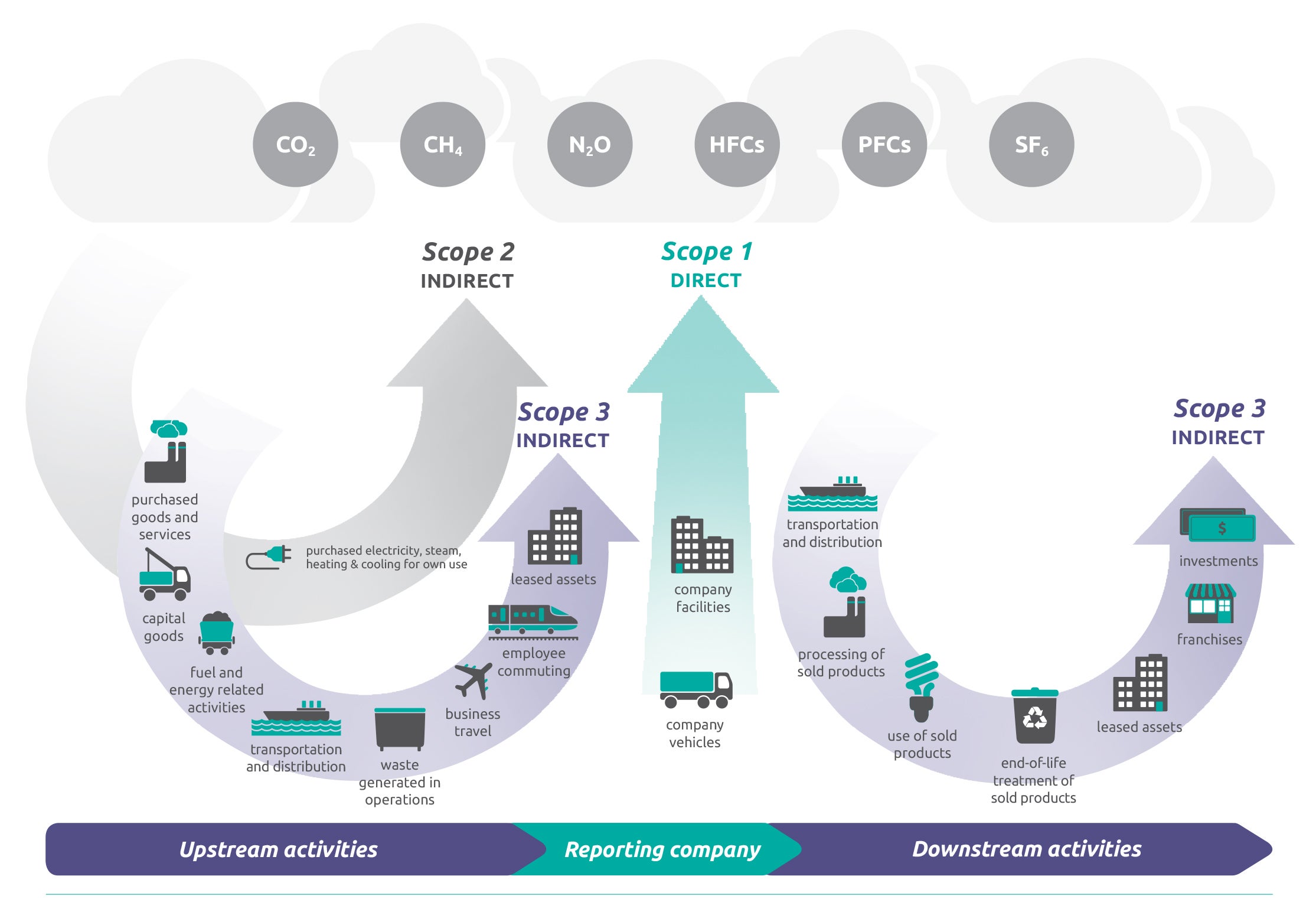

Common metrics are only indirectly connected to environmental risks. Many in-house counsel aren’t familiar with what a quantity of “tCO2e” means. Moreover, there are a series of attenuated steps connecting such a metric with a wildfire or a hurricane that may have resulted from climate change. This applies to other metrics as well, like energy usage.

Micro-impact

With the rise of the service economy, many firms don’t have a direct impact on the environment. The Economist reports that state owned firms produce the bulk of current emissions (likely over 70 percent of all emissions) and that five percent of non-state owned companies in industries like oil, utilities, cement, and mining generate 80 percent of the remaining emissions.

In addition, the nature of climate change results in goals being a long way off. The UN report on 1.5°C suggests a goal of halving emissions each decade from now until 2050. Thus, a corporate program is measured by metrics that are only incrementally improved over years and are often difficult to perceive as contributing to meaningful change.

Technical complexity

Where the first step on the EPA’s website for corporate climate programs is “Review GHG accounting standards,” it’s clear that building an environmental program requires special expertise. Even basic charts explaining emission scopes can’t help but be complex. This means that getting it right will cost you, not only for a consultant but also for someone to manage the program and complete any ongoing reporting.

Lack of awareness or resistance

Employees and company leadership may not be aware of how they can contribute. Others may resist an environmental initiative. Climate change is a complex matter and not everyone agrees on what should be done.

I considered these potential hurdles when first starting a program for Zix, a security, compliance, and productivity tech company. As I was grappling with understanding what an environmental program is, other executives I spoke with would ask, “What does this mean for us?”

The question summed things up. In formulating a response, I realized that the following answers aren’t practical and wouldn’t work:

- “I won’t know until I get a consultant;”

- “We have to calculate emissions and make sure our numbers improve;” or

- “Whatever we do, I expect costs will increase.”

I, therefore, got to work learning more about the situation so I could provide a better answer.

How to get started

Based on what I learned and ended up doing, here are some of the steps to help you start your own program.

Use the TCFD recommendations

The Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosure (TCFD) recommendations outline a structure for an environmental program in support of making climate disclosures. The framework consists of:

- Governance,

- Strategy,

- Risk Management, and

- Metrics.

You can apply it to the high-level features of your environmental program. The framework is relatively straightforward, and mostly amounts to including environmental considerations in many existing corporate processes (even if you aren’t a public company). Moreover, TCFD is becoming a de facto standard with the likes of BlackRock asking for disclosure “in alignment” with it and ISS aligning its climate voting policy around it.

Assess your risk

Critical to understanding what an environmental program will mean for your company is an understanding of your risk. Implementing the recommendations of TCFD is a great place to obtain an initial view of risk. It breaks out certain industries and provides tailored guidance.

Moreover, Appendix 1 is particularly helpful with examples of climate-related risks, opportunities, and potential financial impacts. Think about the risk implications of continuing your operations without taking environmental considerations into account.

Benchmark

Review what others in your industry are doing, as well as ESG leaders. This isn’t only about keeping up with your neighbors. Find out how you can excel and differentiate yourself from the pack.

Focus

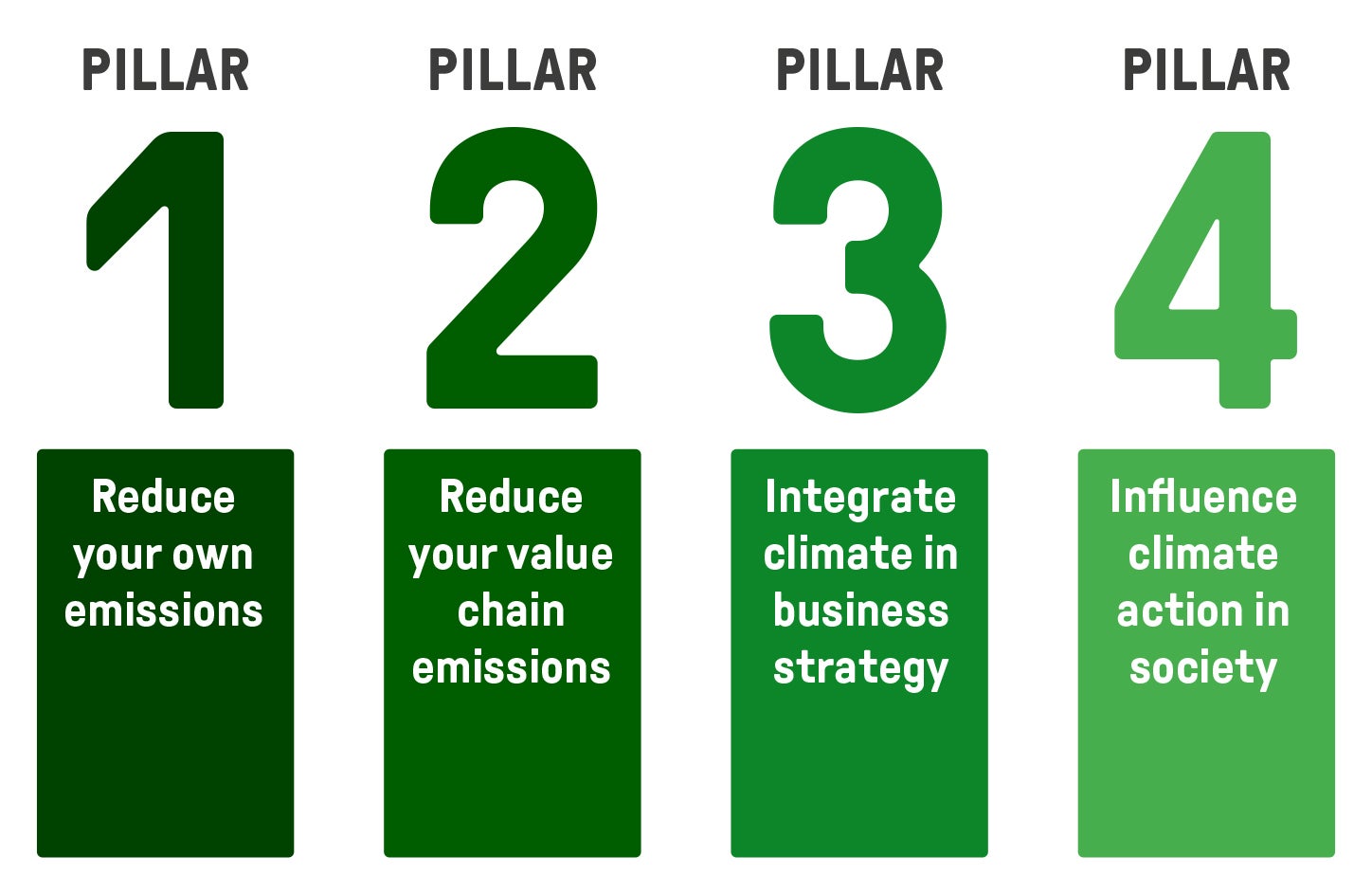

With a basic idea of program structure, risks, and what others are doing, you can start to think about what your company’s environmental focus can be. The 1.5°C Business Playbook recommends a relatively simple approach that provides needed clarity for non-experts. It identifies four pillars and advises you to work step-by-step through one pillar at a time:

The pillars loosely align with Scope 1-3 emissions of the Green House Gas Protocol. Where you start depends on your specific circumstances — you don’t have to tackle everything at once. A conventional business might start at pillar 1 (a company’s own emissions); and a tech start-up at pillar 3 (business strategy for its product line).

Develop and share a basic plan/vision

Make a short statement describing how you’ve decided to focus the program and how it aligns with the goals of your business. For my program at Zix, I would first explain how our program focuses on improving the efficiency of our on-premise data center. As our program has evolved, I now explain how we intend to take environmental into account when we consider our mix of cloud, co-location, and on-premise processing and storage.

Our largest environmental footprint is our energy consumption for data processing, so that is where we focus. And evaluating our mix of cloud, co-located, and on-premise is aligned with our business goals of international growth, because it is easier to expand in different regions with the cloud or co-lo rather than establishing our own data center in each region. This is something I can easily explain to our board, employees, and investor stakeholders.

Be persistent

The metrics are often a challenging, and costly, part of environmental programs. So don’t let them get in your way at the start. You can work on improving even if you don’t have detailed metrics.

In my case at Zix, we know the environmental profile of our vendor supply chain, which means that when we expand usage, we have an idea of how using a given cloud vendor or co-location facility will impact our energy consumption footprint (even without dashboard reporting across our entire network).

Our partner Microsoft, in particular, has done lots of work in the area, committing to environmental goals and providing an Azure dashboard sustainability reporting to customers.

Conclusion

Narrowing the focus of your program and developing a plan that aligns with your business goals will allow you to simplify your explanation of what your environmental program will really entail. This will initially assist you in overcoming the hurdles that such programs often face. As your program expands, and you obtain more help, you can refine your approach and expand your goals for the program.