CHEAT SHEET

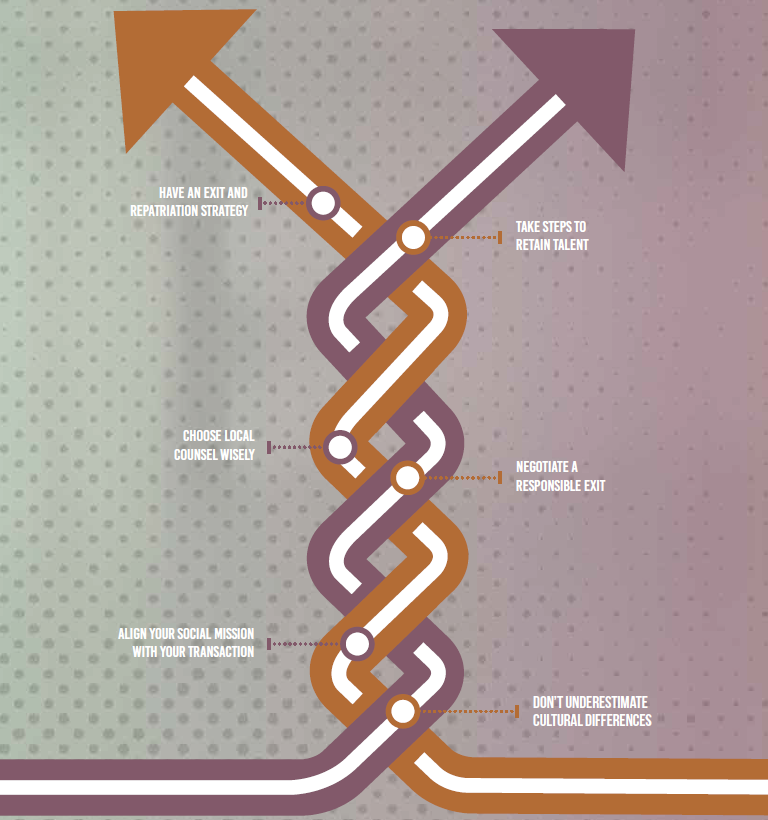

- Local counsel. Finding the right local counsel can help you navigate cultural and communication differences more easily.

- Due diligence. Conduct deep due diligence and tailor your compliance policies to governing laws, sanctions, and international anti-money laundering and bribery acts.

- Personnel. A good understanding of staff skills, and how to care for and communicate well with them, will help foster loyalty to the business and make the post-closing integration process smoother.

- Exit strategy. Clarify the legal and regulatory requirements for exiting and repatriating dividends or proceeds — as well as tax implications.

One of the most exciting times for a company — and its employees — is when it decides to expand overseas. While thrilling, it is also a time of challenges, particularly for in-house counsel who are tasked with coordinating every detail of the mergers and acquisitions transaction agreements. With a focus on emerging nations, this article offers practical tips to assist in-house counsel in identifying the risks of cross-border transactions, navigating those challenges, and in closing the deal.

In 2018, despite global uncertainties, such as trade wars and Brexit, cross-border deals represented a “record US$1.6 trillion (39 percent) of last year’s deals (including six of the 10 largest deals).”

Cross-border mergers and acquisitions challenges

Globalization — the interconnectedness of worldwide businesses — has substantially changed the mergers and acquisitions framework, and created a compelling case for cross-border transactions. Cross-border mergers and acquisitions contracts are therefore on the rise, and increasingly attractive to multinational companies.

In 2018, despite global uncertainties, such as trade wars and Brexit, cross-border deals represented a “record US$1.6 trillion (39 percent) of last year’s deals (including six of the 10 largest deals).” Although the types of deals may vary, organizations usually consider cross-border mergers and acquisitions transactions to be highly challenging, in part because they add layers of complexities and risks in comparison to a deal in a domestic market. Sometimes the challenges and complexities of the legal and/or regulatory environments may be too great, and opportunities may have to be turned down.

Cross-border deals may break down due to, for instance, an unfavorable regulatory or legal environment, the difficulty of finding suitable local counsel, tax burdens, or financial or employment issues. In-house counsel plays a critical role in the risk assessment of such transactions, in developing a mitigation strategy, as well as in demystifying the challenges and helping the business team navigate them.

Specific challenges of cross-border transactions

In-house counsel and the rest of the business team face the challenges of working in different cultures, time zones, and multiple legal systems and/or languages. Such challenges may include significant communication issues, which can arise from negotiating in different cultural environments with dissimilar negotiating styles. What is customary in one country may not be acceptable in another, rendering the negotiations lengthier and making it harder to find common ground.

To add to the cultural and communication challenges, the team may be faced with legal, regulatory, labor, antitrust and anti-competition, tax, and accounting challenges. Logistical problems can also arise when closing a transaction requiring wire transfers of money from different countries and/or time zones. Furthermore, dealing with different legal systems implies relying heavily on local counsel to assist in the drafting of documents and choosing contract language regarding dispute resolution, intellectual property, and choice of law or forum. Together, these can add costs, delays, uncertainties, and hence, additional risks to the transaction. In that case, the common factor — the in-house counsel — often acts as the solid link unifying the pieces of the transaction chain.

Working in difficult geopolitical and economic environments

In some emerging economies, cross-border mergers and acquisitions transactions may present risks and complexities because the transaction is occurring during political or financial instability. Myriad factors can significantly delay the deal process, from opening negotiations through closing.

For instance, the geopolitical environment, including political instability or widespread bribery and corruption, can be complicating factors. Some transactions requiring regulatory or administrative approvals may stall after a political uprising or instability. Political issues can also include protectionism, problems with local bureaucracy, state intervention in business affairs, and social unrest. Currency instability, especially if the transaction takes more time than expected and closing is delayed, may also increase costs and constitute a substantial risk of jeopardizing the entire deal.

In certain regulated industries, where special licenses or permits are required by law, often such licenses or permits may not be “acquired” simply through acquisition of the local entity holding the license or permit. Instead, separate review and application process with the government agencies must be followed. This will mean more time and uncertainty for the transaction, and, depending on whether or not the license/permit is essential, successfully obtaining such approval may need to be stipulated in the deal documents as a condition precedent to the investment.

Don’t underestimate cultural differences

A lack of existing legal approaches around risk management, financial reporting requirements, or corporate governance can raise additional issues that need to be addressed when considering a deal. Restrictive workforce laws or undeveloped intellectual property regimes can also add to the uncertainties.

In addition, finding law firms with international or specific in-country expertise or proficiency in the company’s official language may prove difficult. Dealing with a trusted advisor in an emerging country can mean the difference between a successful deal or failure.

Train your team in compliance

In addition to sanctions regimes, local or otherwise applicable anti-bribery statutes (e.g., the UK Bribery Act 2010), and anti-money laundering regulations, US entities with overseas subsidiaries must comply with the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act of 1977 (FCPA).

Generally, the FCPA prohibits any payments or offers of cash, favors, gifts of any kind, or anything else that has value to the intended recipient, where the intended recipient is a foreign official, or where the intent of the gift is to influence the foreign official to use his or her position to benefit the offeror. In short, the FCPA prohibits knowingly and corruptly giving anything of value to a foreign government official to obtain or retain business. In the countries high on Transparency International’s annual index of countries with perceived corruption, the highest FCPA due diligence scrutiny may be advisable and internal due diligence tailored accordingly.

Dispute resolution challenges abound

Furthermore, working with countries with different or developing legal systems may create additional interpretation or enforcement issues, thereby increasing the risk profile of a deal. Not only the laws themselves, but even certain legal concepts may differ and be subject to various interpretations in common law as opposed to civil law systems. For instance, in common law systems, “consideration” is necessary for a contract to be binding, whereas civil law does not have this concept. Similarly, the concept of “trust” is generally unknown in civil law systems.

Vague or undeveloped laws in some specific areas may also require relying on local counsel’s interpretation more heavily, with the risks that implies. Enforceability of certain provisions in an efficient manner, or with equity, may also be a challenge. The legal value of the transaction documents may be diminished if the documents are governed by local law, and there are serious doubts as to one party’s ability to enforce certain provisions of the agreement. There might also be limited confidence in the predictability of interpretation or the impartiality of the judicial system.

Vague or undeveloped laws in some specific areas may also require relying on local counsel’s interpretation more heavily, with the risks that implies. Enforceability of certain provisions in an efficient manner, or with equity, may also be a challenge.

Similarly, if a foreign judgment needs to be enforced in the local jurisdiction, uncertainty as to the impartiality or effectiveness of the local judicial system may add additional risks. Frequently, a court’s judgment may be biased toward a native party, as opposed to a foreign actor. Therefore, foreign investors usually opt for arbitration, hoping for less biased decision makers and more certainty in enforcement of arbitral awards.

Impact investing considerations

Align your social mission with your transaction

For companies and social enterprises working in international development seeking to create long-term changes, additional considerations may come into play, such as embedding impact into transactions. Specifically negotiated provisions in the transaction documents may be required to ensure alignment of the buyer or the investor with the mission. For example, supermajority voting rights may be required to change the mission or the vision of the organization. Social investors may also request a right to sell their shares if certain social objectives are not reached. A social investor may also require embedding certain ethical principles into the business (e.g., customer protection principles) through policies, processes, or operational practices. Social investors may also look for buyers who fundamentally share their values. This can translate into terms applying the highest quality of environmental and social standards, business integrity, or governance.

Some practical tips to locate qualified local counsel in emerging countries include:

- Careful due diligence through online searches;

- Vetting through legal or financial contacts (e.g., law firms, in-house counsel, or financial advisors);

- Asking for referrals from other global law firms;

- Asking specific legal questions to the local counsel to test competency;

- Asking for deal sheets, names of clients, or clients’ industries;

- Using local counsel for smaller projects before the transaction to test competency (if possible); and

- Interviewing local counsel (in person if possible).

Know your customer

Know Your Customer (KYC) procedures refer to due diligence required by internal policies and local laws or regulations to verify the identity of the individuals and entities with which an organization contracts. KYC procedures may vary by the jurisdiction or type of transaction. These procedures are generally part of an organization’s anti-money laundering and counter terrorism policy.

Customer knowledge is critical in a cross-border transaction. Not only do you want to know who you are partnering with, but also you want to avoid any potential liability for your organization. For instance, it may be unlawful for your organization to do business with an individual or entity recorded on antimoney laundering lists.

The organization’s compliance or risk department is generally in charge of KYC procedures. For cross-border transactions, prior to entering into the transaction, KYC procedures generally entail:

- Verifying the identity of entities and individuals (e.g., target, shareholders, board members, and management) through general (documentary or non-documentary methods) or specific procedures (proof of incorporation, verification of ownership);

- Ensuring that the entity or individuals do not match any name on the anti-money laundering lists, which refers to online services combining governmental and international watch or sanctions lists and checks required by local regulatory authorities; and

- Verifying the sources of funds and identifying any suspicious activity, or any applicable additional exclusion lists specific to your organization’s business.

Negotiate a responsible exit

To ensure the sustainability of impact, some social enterprises, wanting their mission to endure, may also want a responsible exit from the emerging country in which they were operating. Social enterprises may therefore focus on selecting buyers aligned with their mission or vision, with similar experience in the industry and a proven track record. They may also look for buyers that have a history of strong business ethics, solid governance, and high environmental and social standards. Some provisions may also have to be negotiated in a share purchase agreement to contribute to a responsible exit (e.g., employee retention and protection post-closing, or provisions to preserve impact, etc.). These provisions related to the responsible exit may be difficult to enforce for exiting investors, however, and this can make deals more complex or assets less attractive to a buyer or an investor.

Practical tips to navigate the challenges

Choose local counsel wisely

Identifying a local counsel for a cross-border transaction in an emerging country can be challenging. In some countries, a specific transaction may be the first of its kind for the local counsel. Extreme caution should be given to this process, as the choice of local counsel can be a determining factor in making the deal successful.

Interviews, preferably face-to-face, provide an opportunity to analyze the level of expertise and sophistication of the local counsel in depth, together with their foreign language proficiency (especially if the transaction documents are only in the company’s official language). In some cases, the government will require bilingual transaction documents, or sometimes in local language only. It is often a good practice to submit translations together with the local language document. In any event, a local counsel who speaks, reads, and writes the company’s official language fluently is required.

The global outside counsel or global financial firm that may be assisting in the transaction can also provide insight into a specific firm’s expertise. If the transaction requires regulatory approvals, good relationships, and extensive professional experience dealing with the regulator, this should be requested from the local counsel. Expectations and timing of the transaction should be spelled out clearly from the beginning to avoid misunderstandings. In some countries, deadlines are flexible and can depend on a variety of factors, including holidays, rough weather, or the death of an important figure in the country or the region.

Always be aware of cultural and communication differences

Staffing an international legal department with attorneys and support staff who are familiar with the culture of the countries where the transaction is taking place, and who speak the language, is a definite plus. Being mindful of the local environment and cultural sensitivities will help manage expectations and timing. Plan accordingly. For instance, in some countries, it may be unrealistic to close a transaction in August or during a religious holiday. Being considerate of time zones when scheduling meetings and conference calls will also help the transaction go more smoothly. In some countries where security is a major concern, such as roadside attacks or kidnappings, proper risk assessments and related staff training may be required.

Always conduct deep due diligence

A “one size fits all” due diligence approach is not recommended. Tailoring the due diligence to the specificities of the local jurisdiction is extremely important. The global outside law firm assisting on the transaction may provide a general template for a due diligence checklist, but this should be adapted by the local counsel to the specific location and environment.

Starting the due diligence process as early as possible will allow time to mitigate the risks and ensure sufficiency of the due diligence. Face-to-face meetings with the target business and its management should help create a better understanding among all parties, as well as its decision-making process and governance structure, which can be important at the negotiation stage.

A “one size fits all” due diligence approach is not recommended. Tailoring the due diligence to the specificities of the local jurisdiction is extremely important.

When dealing with countries rated high on Transparency International’s annual corruption index, additional FCPA due diligence may be necessary. Know your customer (KYC) checks should be performed depending on the specific risks of the emerging country, on the target acquisition, its board and management, and other potential investors or shareholders. The reputational risks for global organizations should not be disregarded.

Take steps to retain talent

Due diligence on the human resources of the target is not only necessary from a business perspective to ensure proper understanding of talents and workforce, but also to anticipate any cultural and organizational issues for the post-closing integration. Identifying technically skilled workers in some emerging countries may prove difficult, and talent shortages might be a common fact. Therefore, having a good understanding of the staff skills, including those of the local key employees, can be a determining factor for a transaction to be successful. This contributes to the effective structuring of short or long-term incentive plans, such as retention bonuses during the transaction and post-closing, or increased compensation for local key employees. The real value of the target may oftentimes be in its people and their talents, so caring for them, communicating well and sensitively, and preserving their loyalty to the business may be critical.

Pay early attention to the post-closing integration issues

Post-closing integration is sometimes viewed as one of the most difficult parts of a transaction, and again the in-house counsel plays a crucial role. Post-closing, and as part of the integration process, in-house counsel should ensure that the local entities policies are updated (e.g., corporate governance, anti-money laundering, data privacy) to include, for instance, FCPA or EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) provisions, if applicable. For increased enforcement of FCPA provisions, in-house counsel should consider training the local legal or human resources teams. In turn, they can train the local staff (in local languages if needed) on FCPA requirements, and post FCPA/anti-bribery flyers to raise awareness in the local offices. Other measures could include having an ethics hotline and a place for incident reports where staff can report violations of any ethics rules in complete confidentiality. Insisting on the need to guard the company’s reputation and global brand and the costs associated with any violations that can impact the entire network may also prove useful to “cascade” the message to the local management team.

Additional measures to consider include: thorough internal controls and procedures, along with employee training, anticorruption language in agreements, and an efficient compliance and monitoring program. Management should be proactive in cultural integration, and in-house counsel can assist in flagging concerns raised during the due diligence. The in-house counsel can also bridge the various functions of the target company and get to know the target’s staff and the structure. All this can help the management assess the extent of business and culture integration required. Collaboration between the deal team, the in-house counsel, and the integration team facilitates the integration process, especially in jurisdictions where certain business practices may be limited by the legal or regulatory environment, and where translations may be required. Information technology systems may also be a critical issue for integration and cause delay in the operation of the local entities. Organizations may consider entering into transition services agreements to cover licensing of critical software, or provisions of information technology services for the transition period.

Familiarize yourself with the governing laws and dispute resolution mechanisms — then promote standardization

Agreeing on acceptable governing laws is one of the most crucial aspects of the negotiations. In most cases, it may not be a good idea to choose the local law, for reasons explained earlier. Global organizations may prefer well-established laws, such as New York or English law. Arbitration may also be preferred. It is atypical in cross-border deals to use local courts in dispute resolutions. Also, to ensure that fewer deals break down, the use of a standard approach in drafting language in the transaction documents, by using globally accepted legal norms of US or UK origin, may also help, regardless of where the transaction is located. As mentioned earlier, forum choices may also be a material point for negotiation.

Have an exit and repatriation strategy

Planning an exit strategy and obtaining a clear understanding of the repatriation issues in the targeted country are also important when considering a deal in an emerging country. In-house counsel should clarify the legal requirements as well as regulatory or other approvals needed to exit and to repatriate either dividends or proceeds, as well as the tax implications for such exits and repatriations. An upfront plan on exit and repatriation should allow the in-house counsel to anticipate any issues and potentially structure the ownership to avoid or limit any roadblocks to an orderly exit or proceeds repatriation.

Conclusion

Overall, deals in emerging countries may offer challenges similar to those encountered in any cross-border merger and acquisition transaction. However, in some situations, such deals may present added layers of complexities. Some organizations may turn down transactions in a country where the government has too much influence over legal or regulatory matters, or where political instability is too great. The risk may not be worth taking.

If the transaction is pursued, the role and involvement of in-house counsel in the success of the transaction are paramount. In that context, working outside of a familiar legal environment and being confronted by a myriad of legal, regulatory, political, or other challenges in the target country, can be disconcerting or even overwhelming. In-house counsel working on cross-border transactions in emerging countries are oftentimes required to be extremely creative and flexible. Finding solutions may involve extensive discussions and brainstorming with the local counsel and deal team. Therefore, the local counsel selection, and clear communications with such counsel, the deal team and the local partners on their respective roles and expected contributions to the deal, are crucial for a successful transaction. An experienced translator is invaluable as well.

The importance of extensive due diligence cannot be overstated. It is absolutely necessary to fully understand the legal and regulatory environment, the target company, its culture, and related risks. A comprehensive due diligence program also contributes to a successful post-closing integration and proper retention of talent. Appropriate use of the skills and knowledge of local counsel, as well as on-site visits, will facilitate obtaining accurate facts and anticipating issues both for the transaction and the post-closing integration.

Cross-border transactions in countries with unstable conditions require additional advanced planning and extended timelines. Any in-house counsel must be well prepared to manage the deal team’s expectations, especially on timing issues, potential delays or setbacks, and regulatory or administrative roadblocks. In many instances, increasing planning timelines and patience during the deal process are essential.

Upfront investment in in-house counsel remains key to the successful completion of these transactions. Done well, the role of the in-house counsel will be strengthened and prized as a bridge between legal and business cultures worldwide.