In 2004, Larry D. Thompson, who served as the deputy attorney general for the United States from 2001 to 2003, gave a speech, “The Corporate Scandals, Why They Happened and Why They May Not Happen Again,” regarding the government’s response to massive accounting scandals that rocked financial markets in 2001 and 2002. During his talk, he expressed his hope that the passage of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act and amendments to chapter eight of the US Federal Sentencing Guidelines would prevent future corporate malfeasance and restore public trust in business.

Given these new rules, Thompson stated: “The board of directors and senior management can no longer simply delegate the ethics and compliance function to officials lower in the organization. They must understand what is going on and what problems and vulnerabilities their companies may have from a compliance standpoint … Now, board members will be required to get ‘their hands dirty’ and become knowledgeable about a company’s compliance problems and vulnerabilities.”

Sadly, Thompson’s optimism was misplaced. At the time he delivered this speech, the seeds were being sown for even larger corporate scandals in the banking sector. These scandals resulted in a near meltdown of the world’s financial system and cost taxpayers and shareholders around the world trillions of dollars. Despite additional governmental regulation that followed, breathtaking corporate scandals continue with regularity in some of the most renowned, and supposedly well-governed, corporations.

Volkswagon and a dozen other auto manufacturers were recently caught in the diesel engine emissions fraud scandal. Wells Fargo and dozens of other banks have been caught engaging in a wide range of illegal and unethical conduct. Virtually every major medical device and pharmaceutical company has been prosecuted for paying bribes to doctors or promoting their products off label. Bid-rigging and price fixing antitrust violations continue to plague the petrochemical industry. And corporate bribery of government officials persists across all industry sectors.

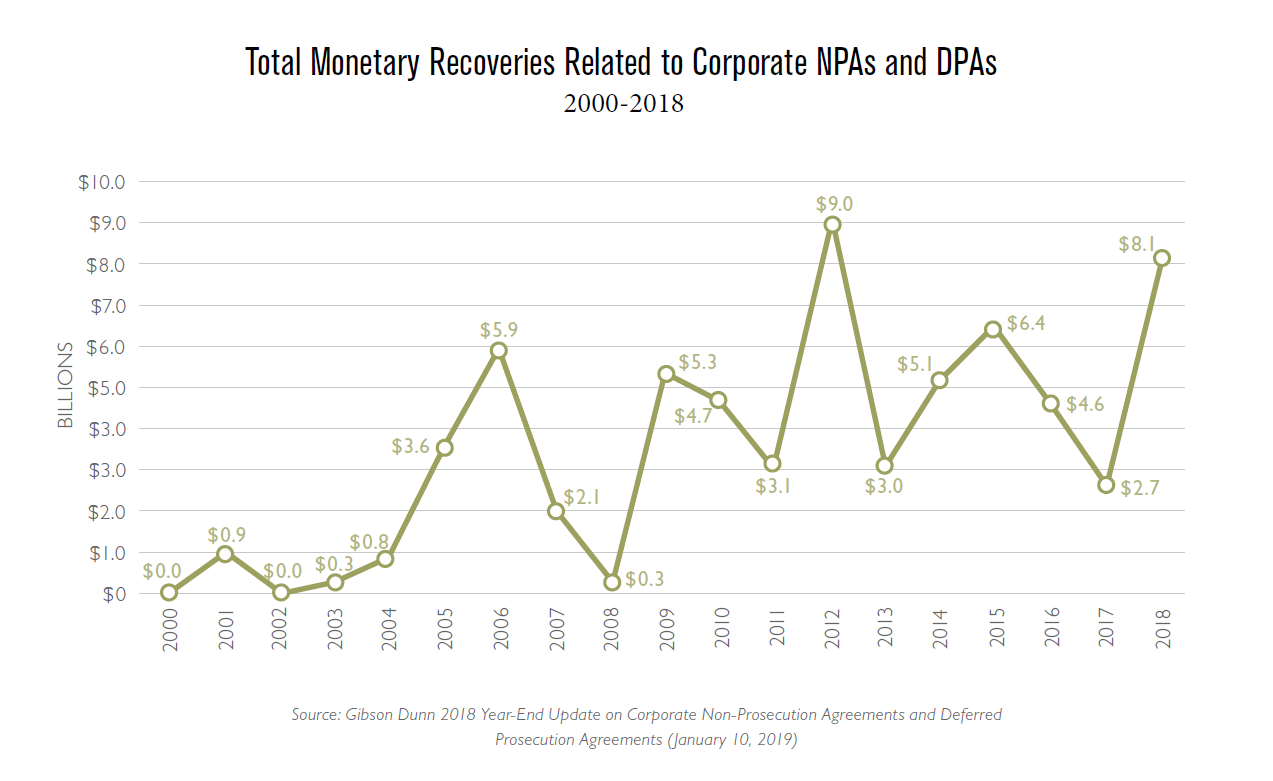

Despite the governmental reforms and millions invested in compliance and ethics programs (CEPs), it is difficult to find evidence of any improvement in corporate compliance and ethics performance. Judging from monetary recoveries related to corporate Non-Prosecution Agreements (NPAs) and Deferred Prosecution Agreements (DPAs), the trend over the last 18 years has been in the opposite direction.

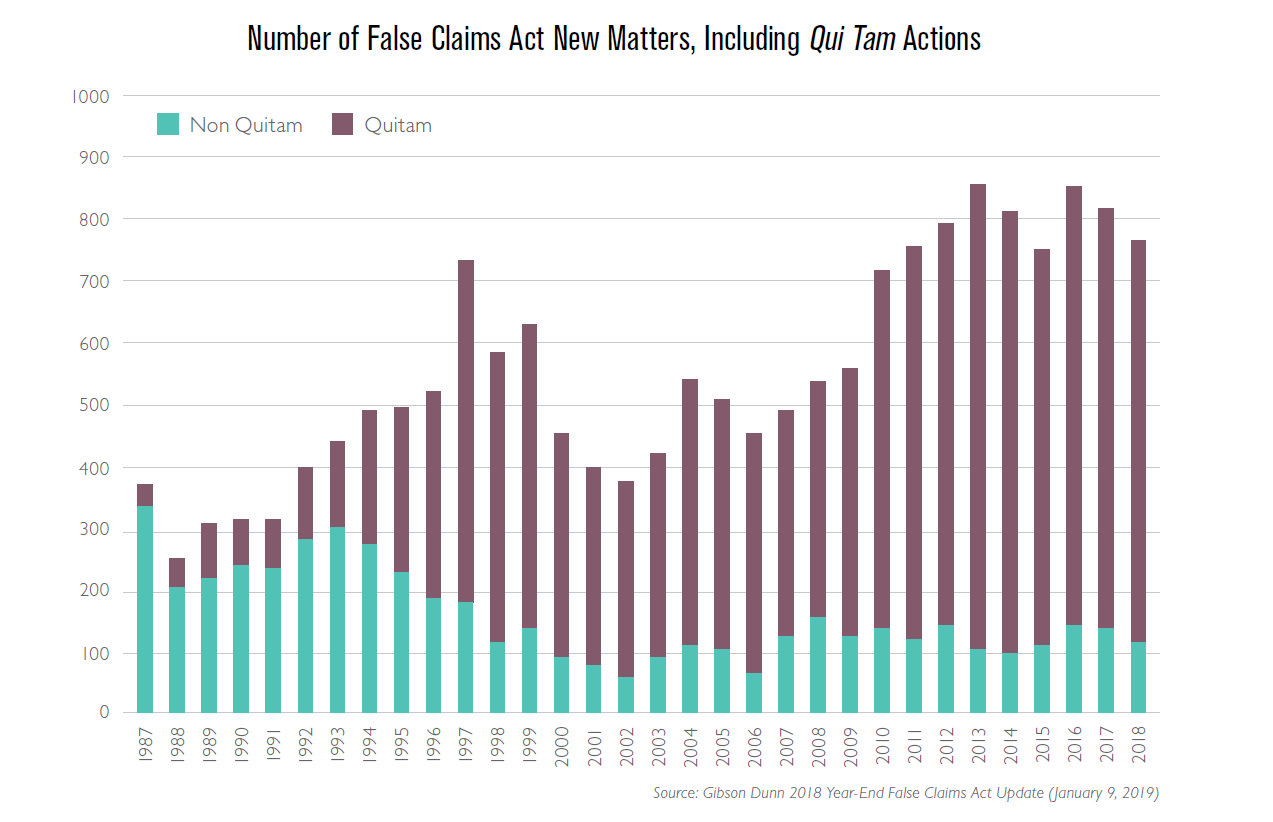

There is also a disappointing trend with respect to corporate fraud prosecutions. In 2018, the US Department of Justice recovered US$2.9 billion — on par with record amounts collected in past years. Moreover, the data shows no reduction in the annual number of False Claims Act actions for the last 31 years.

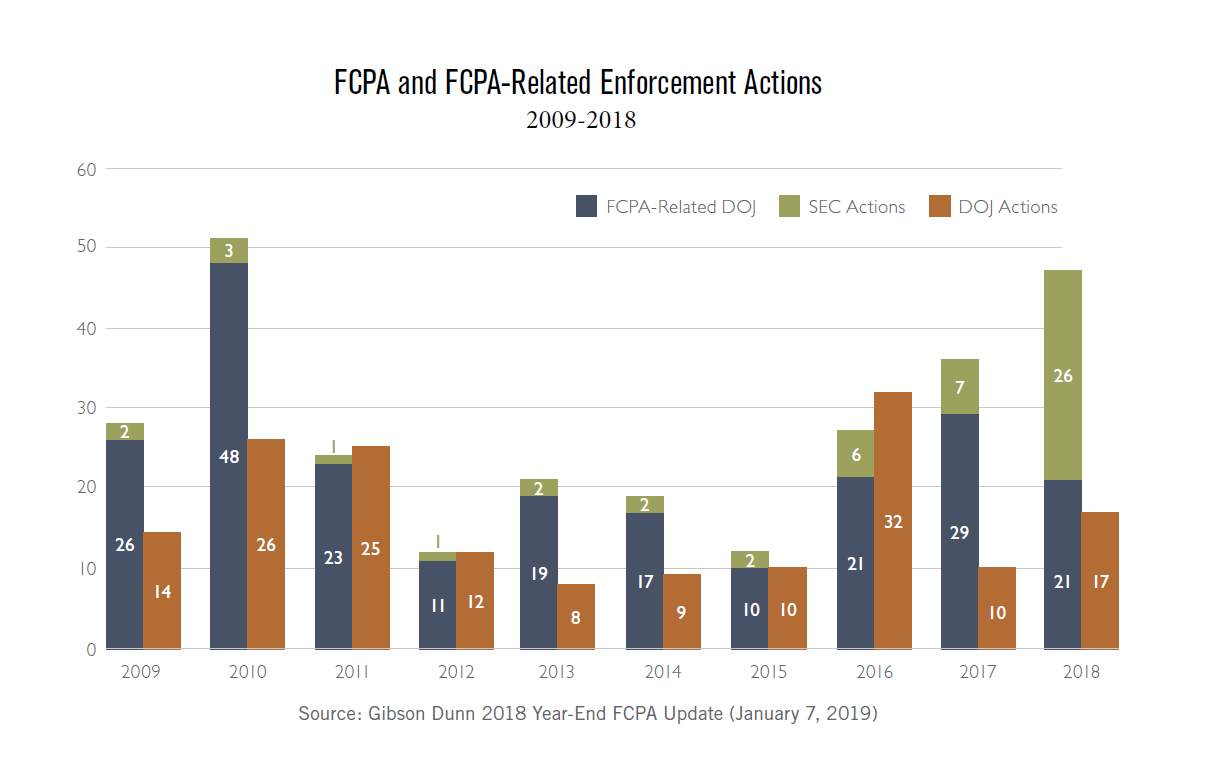

Nor is there evidence of reductions in Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) and FCPA-related enforcement actions.

Admittedly, the data does not represent the universe of corporate malfeasance, and there are likely multiple variables driving the numbers, such as changing governmental enforcement priorities. But, regardless of where you look, one is hard pressed to find any data evidencing corporate compliance and ethics performance improvement.

The steady volume of material corporate wrongdoing by some of the most respected firms in the world is not attributable to a dearth of policies and procedures or compliance and ethics programs. In the last few decades, law departments and compliance offices have produced mountains of such governance documents and invested in thousands of formal compliance and ethics programs. Instead, the root cause is a failure of leadership at the top to build and sustain corporate cultures in which significant legal and ethical lapses would be unthinkable.

The simple fact of the matter is that boards of directors have not gotten their “hands dirty” as Thompson hoped. They continue to outsource compliance and ethics to small, often under-funded, compliance functions to which they pay little attention. A 2018 LRN survey of chief compliance and ethics officers (CECOs) entitled What’s the Tone at the Very Top? concluded, among other things, that CECOs believe that “boards do not fully understand the ethics and compliance programs they are supposed to be overseeing” and that “many boards do not devote significant time and priority to ethics and compliance.” Additionally, the survey found that most CECOs believe their boards “lack appropriate metrics through which to evaluate ethics and compliance” and that “boards do not ask enough of executive management in ensuring effective ethics and compliance.”

This is a crisis in corporate governance. If not remedied, we will see no end of significant corporate scandals, and the next one could involve your employer. To turn things around, we cannot wait for additional governmental regulation. Our best hope of improving corporate governance is for us — corporate counsel and compliance and ethics professionals — to work together with our executive leadership teams to both educate our directors and get them in the game.

This work is not easy, but if we don’t make the business case for adopting sound corporate governance practices with the object of achieving ethical excellence, who will? The approach you take will depend on several factors that vary significantly between firms. These include, but are not limited to:

- Whether your company or its peers have been the targets of recent enforcement actions;

- Your position in the organization;

- The social dynamics of your senior leadership team and the board; and

- The magnitude of the culture shift required to put business integrity at the top of the board’s agenda.

Regardless of your circumstances, you might maximize your chances of success by taking some of the following steps:

- Enlist as many allies to the cause as you can — the higher up in the organization, the better.

- Figure out how to gather meaningful business integrity metrics that can be presented on simple, standalone dashboards. Don’t bury integrity metrics in charts with dozens of other business performance factors.

- Share the integrity metrics with your company’s executive leadership team and the board and teach them how to read and respond to the data presented.

- Make the case that since integrity is the foundation of everything the business does, it should be at the top of the agenda at every board meeting with the CEO presenting the metrics and being held directly accountable for driving performance.

Finally, before taking on this mission, be sure to take a courage pill. Cultures are stubborn and highly resistant to change, which is likely to cause your colleagues some anxiety. But this brand of anxiety is vastly preferable to anxiety driven by a colossal ethics scandal and its aftermath.