CHEAT SHEET

- Past processes. Before IPRs, alleged infringers could assert invalidity defenses in district court. Those defenses often took years to be heard and were decided by jurors with little or no technical background.

- New hope. In September 2012, IPRs implemented rigidly enforced deadlines, limited discovery, and limited invalidity grounds with the hope of streamlining processes. Approximately six months after an IPR petition is filed, a panel of patent experts issues an institution decision.

- Receiving a complaint. Generally, an accused infringer should start searching for prior art as soon as possible. Once you are served with a patent infringement complaint, you have one year to file an IPR.

- Joint-defense considerations. Patent owners — especially NPEs — often sue multiple defendants on the same patents. However, while joining forces to prepare IPRs can seem like a good idea, it may result in disagreements on strategy that have an impact on the final product.

Managing patent infringement assertions has changed dramatically since the September 2012 introduction of inter partes review (IPR) proceedings, trial proceedings conducted by the US Patent and Trademark Office (Patent Office) based on patents or printed publications. Before IPRs, a patent demand letter or district court complaint, whether a close call or a meritless nuisance lawsuit, began a long process that could cost millions of dollars and untold business uncertainty. Once engaged, it was often prudent to consider a cost-of-defense settlement rather than seek litigation based on the merits. This created an industry of non-practicing entities (NPEs) that could assert even questionable patents — just for the cost of filing a district court complaint — with the hope that many defendants would settle without challenging the patents’ validity.

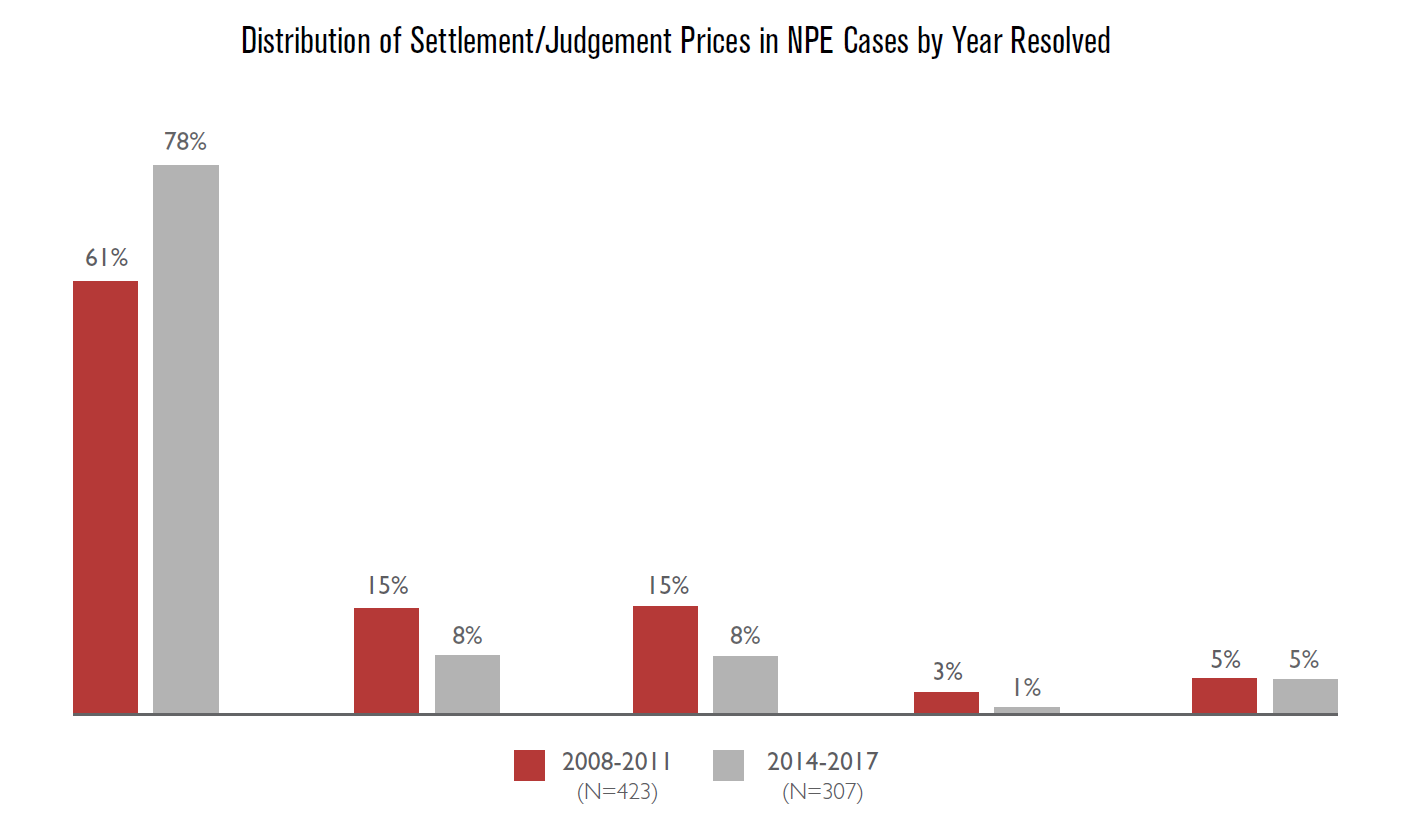

With the advent of the IPR, the cost of asserting any patent, particularly those of questionable validity, has risen. And those costs, as well as the risk of patent invalidity, can now be front-loaded in the dispute. IPRs have reduced the cost to challenge questionable patents and also reduced their settlement value.

As shown in the chart above, the introduction of IPRs has led to a significant shift to more resolutions in the US$0 to US$500,000 range, with a corresponding reduction of resolutions in the US$500,000 to US$10,000,000 range.

Managing patent assertions before IPRs

During patent litigation, alleged infringers evaluate the patent’s validity, the likelihood of an infringement finding, the potential damages, and business disruption. While all of these remain considerations, assessing patent validity has come to the forefront, as IPRs can often resolve the dispute within 18 months of filing and before expending significant resources in district court. Before IPRs, while alleged infringers could assert invalidity defenses in district court, those defenses often took years to be heard and were decided by jurors with little or no technical background — a risky proposition.

As an alternative, the accused infringer could request to reexamine the asserted patents in the Patent Office. The reexamination request would have to raise a substantial new question of patentability and could not rely solely upon references considered during the patent’s original examination. Once the Patent Office determined that the request raised a substantial new question of patentability, an examiner would issue an office action, rejecting one or more claims. Then the patent owner could counter the rejection and add new claims to vary the scope of protection from the originally granted claims. The general format of the reexamination process, as well as the consideration of additional claims, made the proceedings stretch even longer than many district-court actions, often between 2.5 and 3.5 years. After the reexamination process, the matter could be appealed to the highest level of the Patent Office, the Board of Patent Appeals and Interferences (BPAI), the predecessor to the present Patent Trials and Appeal Board (PTAB). The BPAI was notoriously slow, which made the complete process virtually unworkable as a substitute for the much quicker district-court proceedings.

Thus, many stakeholders in technology industries, particularly in fast-moving technologies such as electronics and telecommunications, successfully urged Congress to create a streamlined Patent Office procedure to more quickly evaluate the validity of issued patent claims.

Overview of the inter partes review process

The procedure, implemented in September 2012, is called an inter partes review because it is conducted not by a Patent Office examiner but by a panel of three administrative patent judges who generally have a technical background as well as patent law experience. The review process is streamlined with rigidly enforced deadlines, limited discovery, and limited invalidity grounds the panel will only consider printed publications (patents, articles, brochures, etc.). Approximately six months after the petition is filed, the panel issues an institution decision. If the panel finds that the petitioner demonstrated a reasonable likelihood of showing that at least one challenged claim is invalid, it institutes an IPR trial; otherwise, it declines to institute an IPR. A trial period begins immediately after institution and, approximately nine months later, concludes with oral arguments. During the trial period, the patent owner will counter the petitioner’s invalidity arguments to preserve the validity of the patent claims. The patent owner may also — in limited circumstances — amend the challenged claims to avoid the asserted prior art. A final written decision is issued within 12 months of institution. The entire IPR process lasts approximately 18 months from initial filing to the final written decision.

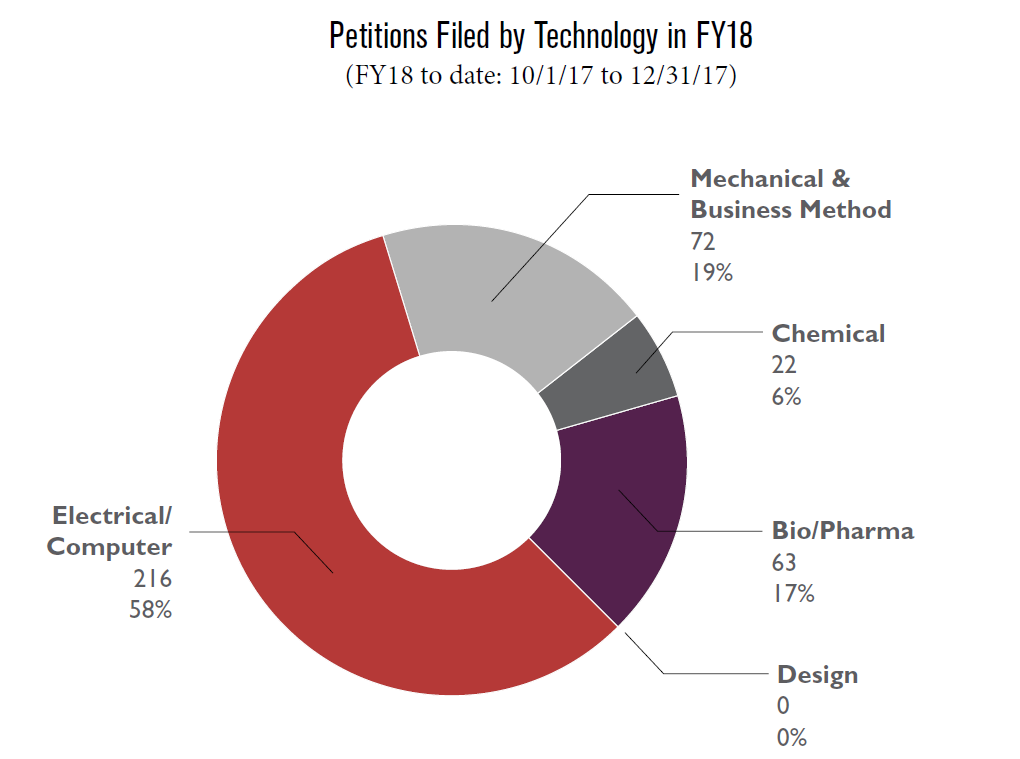

As of December 2017, 7,311 IPRs have been filed since the introduction of the IPR process. As shown below, while electrical/computer patents still make up the majority of challenged patents, challengers from a broad range of technologies are using the IPR process.

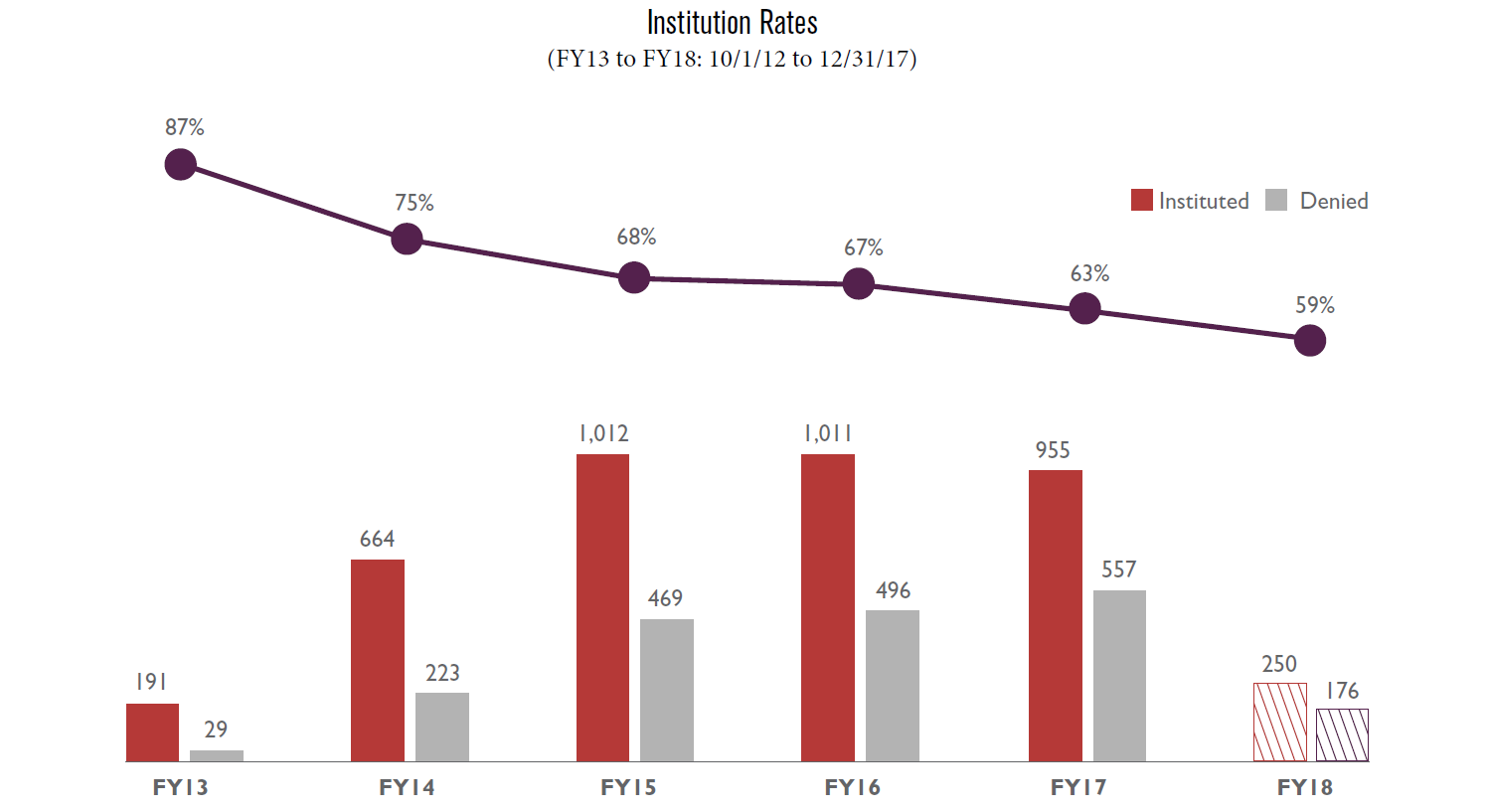

The earliest adopters of IPRs were heavily concentrated in the electronics and communications technology sectors. Given the complexity and rapid development cycles of their products, these businesses were routinely subjected to patent-infringement assertions. A number of patents asserted by NPEs had exceptionally broad claims, but few companies chose to fight through the litigation process to challenge validity to a conclusion. As a result, many patents asserted by NPEs were generating substantial revenue even though the potential licensees believed the patents were likely invalid. Thus, many early IPRs challenged these weak patents, and petitioners’ success rates were exceptionally good in the early years. Over the past five years, however, the petitioners’ success rates have fallen somewhat, likely due to the early removal of weak patents as well as modified PTAB procedures that provide patent owners with greater opportunities to defend their claims.

Because IPRs, like any litigation, have uncertain outcomes and come with tradeoffs against actions in district court, the use of IPRs must be evaluated on a case-by-case basis.

Practical considerations for accused infringers and patent owners

Under what circumstances should an accused infringer consider preparing and filing an IPR petition? The answer depends on the seriousness of the infringement allegations and the nature of the accuser. Some infringement allegations are unserious on their face. If the infringement case is weak, you may decide not to go through the trouble and expense of filing an IPR. Likewise, you may consider forgoing an IPR if the accuser (or its counsel) is known for a “volume” business — that is, filing lots of cases and settling them quickly and cheaply. In those cases, from a pure business standpoint, it may be prudent to simply pay a small amount to make the case go away (although we would caution against doing so as a matter of course).

In short, you should consider IPR as part of a litigation strategy whenever faced with a credible infringement accusation that could actually be litigated.

Timing issues; motions to stay

When should an accused infringer start preparing to file an IPR? Generally, you should begin searching for prior art — remember, only patents and printed publications — as soon as possible. Once you are served with a patent-infringement complaint, you have one year to file an IPR. While that gives you plenty of time to file an IPR petition, the sooner you file, the better.

Because the petitioner (the accused infringer) should challenge all asserted claims, it can make sense to wait until the patent owner identifies the asserted claims. Most courts require patent owners to serve early infringement contentions that identify asserted claims and accused products.

One of the benefits of filing an IPR is that courts may stay the litigation during the IPR. In deciding motions to stay, courts consider three factors: (1) the status of discovery and trial in the district court; (2) whether a stay will simplify the issues before the court; and (3) whether a stay would unduly prejudice or present a clear tactical disadvantage to the nonmoving party (that is, the patent owner). Moving to stay early in the district court litigation will make it more likely that the first factor above — the stage of the litigation — will weigh in favor of a stay.

Most courts will not stay a case before an IPR is instituted (although courts in California have been known to do so). Therefore, a stay before the institution decision is unlikely. So the district court will not likely address a motion to stay until after the institution decision — or at least six months after the petition is filed. That means that it is even more important to file the petition as soon as possible, particularly in fast-moving courts like the Eastern District of Texas and the Eastern District of Virginia.

The following table shows the current outcome of estoppel:

| INVALIDITY GROUNDS | PTAB FINAL WRITTEN DECISION | ESTOPPEL |

| References A+B | IPR instituted on grounds A+B | Yes |

| References C+D | IPR not instituted on grounds C+D | No |

| References E+F | Not raised in IPR | Maybe |

US Supreme Court decisions with potential impact on IPRs

At the time of writing, the US Supreme Court is considering Oil States Energy Services, LLC v. Green’s Energy Group, LLC, which raises a constitutional challenge to the IPR system. Specifically, Oil States argues that patents are private rights that may be taken away only by an Article III court, not through an Article I administrative proceeding in the Patent Office. Greene argues that the Patent Office review is simply a reconsideration of a prior agency decision and is well within the purview of the agency to correct any errors in granting the original patent. While most predict that IPRs will survive this constitutional challenge, a win for Oil States could end the IPR regime entirely.

The Court is also considering the PTAB’s administration of the IPR process in SAS Institute v. Matal. That case involves the statute’s requirement that the PTAB must “issue a final written decision with respect to the patentability of any patent claim challenged by the petitioner.” Despite the statute’s plain meaning, current PTAB practice is to issue a final decision on only some of the claims. A decision requiring a decision on all challenges raised could have a significant effect on estoppel in related district court litigation.

Of course, if the PTAB does not institute an IPR, or institutes on fewer than all asserted claims, a stay is unlikely. Also, stays are less likely when the patent owner and the accused infringer (the petitioner) are competitors or when the litigation has proceeded to an advanced stage before the IPR is instituted.

Another timing issue to consider — and another good reason to file an IPR petition as soon as practicable — involves the situation where multiple accused infringers each file IPR petitions against the same patent or patents. The PTAB can decline to institute an IPR because the petition’s invalidity grounds are redundant, or because the PTAB — in its discretion — decides that too many IPR petitions have been filed against a particular patent. It pays to be the first to file an IPR petition against a particular patent because it reduces the likelihood that the PTAB will decline to institute the IPR on redundancy or discretionary grounds.

Finally, filing an IPR petition as soon as possible helps to win the “race to finality.” A final, non-appealable PTAB decision finding invalid claims at issue in parallel district court litigation will moot that litigation. In Fresenius USA, Inc. v. Baxter International, Inc., 721 F. 3d 1330 (Fed. Cir. 2013), the Federal Circuit affirmed the Patent Office’s cancellation in reexamination claims litigated in a parallel district-court case. Because the litigation was not final, the Federal Circuit’s decision affirming the Patent Office’s ruling bound the district court and mooted the litigation.

Patent assertions internationally

As many corporations have multinational operations, so too can they expect patent-infringement assertions in jurisdictions outside of the United States. Fortunately, procedures similar to inter partes review to challenge the validity of patent claims exist in many other jurisdictions. Thus, in many ways, the considerations of managing patent assertions in other jurisdictions follow a similar course as those in the United States.

For example, a party accused of patent infringement in Germany may challenge validity through a nullity proceeding in the Federal Patent Court in Munich. As in an IPR, German nullity proceedings are presided over by a panel of judges with technical backgrounds. Evidence is typically limited to printed publications and occasional expert testimony. But in rare instances, witnesses may be called to testify about issues such as public accessibility to the asserted prior art.

Unlike US courts, German district courts adjudicate only infringement and damages, not validity. But German district courts will consider a stay if it finds that the co-pending nullity action will likely succeed. These stays, however, are rather rare — German courts usually require that: (1) the prior art relied upon was not previously considered by the patent office; (2) the prior art destroys the novelty of the invention in the patent; or (3) the prior art makes the invention so obvious that no reasonable arguments can be found at all to recognize an inventive step. As in the United States, quickly developing invalidity grounds for the nullity action is critical to avoid an adverse district-court decision before a challenge to the validity of the patent can be mounted.

While Germany has always been a significant commercial market, it has risen in importance in recent years as a common forum for NPEs to assert their patents.

The Japanese Patent Office also offers a proceeding called a Trial for Patent Invalidation to challenge the patent validity outside of district court. According to JPO statistics, patent invalidation trials are often completed within 10 months — almost six months faster than the corresponding district court litigation. Moreover, as in the United States, Japan does not require a first-filed infringement lawsuit, which permits parties concerned about a patent to challenge its validity before the party gets sued for infringement. In fact, according to JPO statistics, almost 60 percent of invalidation trials are conducted with no first-filed infringement litigation.

Other tactical considerations

Aside from the possibility of staying the district court litigation, IPRs can present other tactical advantages. For example, a patent owner responding to an IPR petition may be forced to construe key claim terms narrowly to distinguish its claims from the prior art. This is because the legal standard for claim construction is broader in IPRs than in district-court litigation. The accused infringer can then use the patent owner’s narrow IPR claim constructions in the district court proceedings to narrow the claim construction and support noninfringement defenses.

While PTAB constructions do not bind district courts, some courts have stated that PTAB constructions are entitled to some deference, so they can have a persuasive effect on the district court. And the statements made by the parties, and decisions made by the PTAB, are often treated as “intrinsic evidence” by district courts in their own claim construction proceedings. It is important for IPR and litigation counsel to closely coordinate when selecting prior art to assert and construing key patent terms.

As noted, the PTAB may decline to institute an IPR if it decides that the petition’s invalidity grounds are redundant to another petition’s grounds. So when yours is not the first petition filed against a particular patent, make sure to explain in the petition why its articulated invalidity grounds are not redundant to those in earlier petitions.

IPR estoppel and other grounds of invalidity

Another issue for the accused infringer to consider is IPR estoppel, where an IPR petitioner is “estopped” from asserting any of the grounds actually presented — plus any grounds that reasonably could have been asserted — in any IPR that results in a final written decision. This estoppel applies to the petitioner, anyone in privity with the petitioner, and any other party that is considered a real party in interest in the IPR (such as an entity who directs and controls IPR proceedings). The estoppel applies only to claims that are the subject of a final written decision in the IPR. Also, because non-instituted grounds (that is, grounds for invalidity proposed in the petition but not chosen by the PTAB for trial) are not addressed during an IPR, non-instituted grounds are not subject to estoppel. There is a split of opinion in district courts as to whether to apply estoppel to grounds that reasonably could have been raised in the petitioner’s IPR, so this is an issue that requires careful consideration.

Also, because estoppel applies only to grounds addressed in a final written decision, if the district court does not stay the litigation pending the IPR, the petitioner may assert the same invalidity grounds in both the pending IPR and pending district court litigation.

Finally, remember that only patents and printed publications may be asserted in IPRs. A petitioner cannot challenge a patent’s validity under the on-sale bar, prior public knowledge, prior use, indefiniteness, lack of enablement or written description, or patent ineligible subject matter. It is important not to lose sight of these defenses in district court litigation — they can be developed to create a multi-pronged validity attack if the litigation is not stayed or if the PTAB confirms any of the asserted claims.

Joint defense considerations

Patent owners — especially NPEs — often sue multiple defendants on the same patents. So joining forces to prepare and file IPRs on the asserted patents can seem like a good idea. And it can be — the defendants can share expenses, crowd-source prior-art searching, and get the benefit of multiple points of view on IPR strategy. But there are downsides.

First, as in other endeavors, an IPR-by-committee may not result in a good product — even if everyone agrees on a strategy. More likely? Disagreements about strategy. So any joint effort should spell out the parties’ respective roles and responsibilities before drafting begins. Put it in writing. Make sure that there is one leader — one party or law firm — that will have final say over strategy. The agreement should also lay out a succession plan in case the lead defendant settles.

One easy-to-miss issue is the one-year time bar and real parties in interest. If one of the joint petitioners was served with its infringement complaint more than one year before the parties file their joint IPR, then the PTAB will decline to institute the IPR. Also, if one of the joint filers has already filed an IPR, there is a risk that the PTAB will exercise its discretion to decline institution because of redundant grounds. In these situations it is vital to explain in the petition why the petition’s grounds are not redundant to the grounds presented in earlier IPRs.

Considerations for patent owners

A patent owner should expect to face an IPR on any patent it asserts. It makes sense to be prepared. Because of IPRs, it is all the more important to thoroughly vet any patents before asserting them. This should include searching for potentially invalidating prior art. Assert as many patents and claims as possible — IPR is a cheaper alternative to litigation, but the costs for multiple IPRs can be significant. Facing the need to file multiple IPRs can make a defendant look more closely at early settlement. And having more claims and patents at issue means a greater chance that some will survive IPR.

Patent owners should continue to watch two cases moving through the PTAB addressing whether entities possessing sovereign immunity can exempt their patents from an IPR proceeding. In the first group of IPRs, the University of Minnesota sued numerous entities for patent infringement in district court. The defendants then filed IPRs on the asserted patents, and the university sought to dismiss the IPRs based on sovereign immunity, the legal doctrine that states or sovereign nations cannot commit a legal wrong and are immune from civil suit or criminal prosecution. The PTAB rejected that argument, ruling that the university waived its immunity by bringing suit in federal court. In the other IPR proceeding, after asserting the patent in district court and the defendants’ filing an IPR, Allergan transferred ownership of a valuable patent to the Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe. The tribe claims its patent is immune from an IPR challenge. If either of these parties successfully asserts immunity, it is likely that many patent owners will transfer their patents to sovereign entities to avoid IPR challenges while continuing to assert their patents in district court.

IPR decisions provide opportunities for settlement

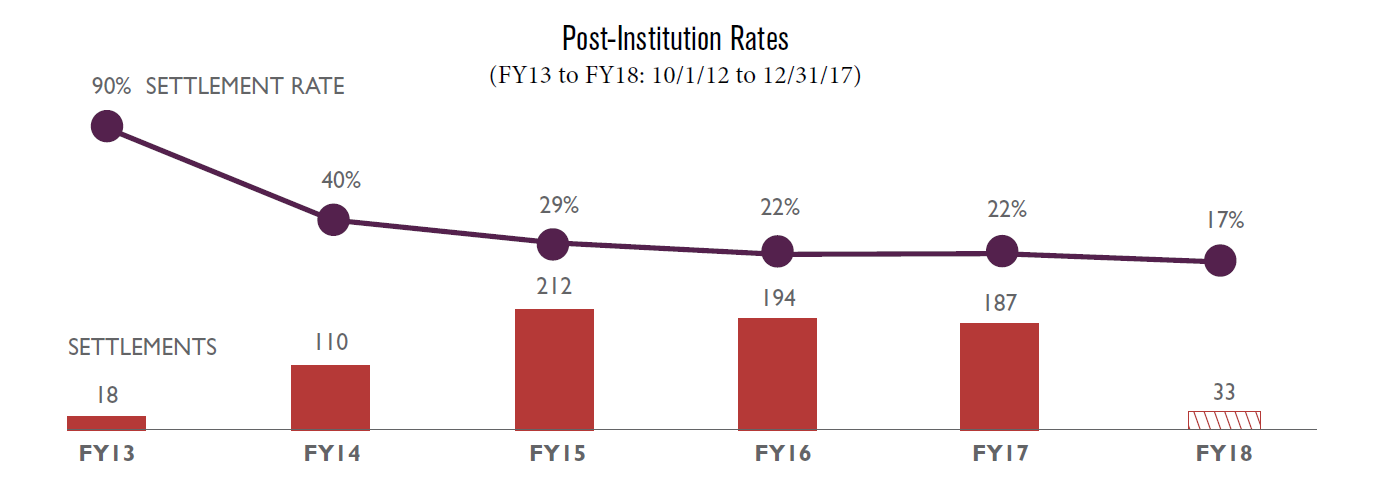

Approximately 15 percent of disputes settle after the filing of an IPR but before institution. In these situations, the patent emerges from the process unscathed, and other defendants will not know if the asserted challenges will be successful. If the IPR continues, the institution decision is the first decision on the merits of a party’s assertions, which can provide a framework for settlement. The pie chart above shows the Patent Office’s statistics for post-institution settlements.

Of course, if the IPR is not instituted, the entire dispute returns to the district court for continued litigation.

Conclusion

Based on the first five years, IPRs have proven to be an effective tool for accused infringers to challenge patent validity cheaply and effectively. IPRs have driven down the cost of defending against and the settlement value of many patent-infringement assertions. Those faced with patent assertions cannot afford to overlook IPR as a defense tool. And patent owners, too, must adapt their tactics to address the challenges of IPRs.