CHEAT SHEET

- Don’t mix and match. During cross-border discovery, parties should not attempt to mix different jurisdictions’ discovery and privilege laws.

- Federal Rule of Evidence 502(d). Use Rule 502(d), which states that the disclosure of a privileged document will not act as a waiver in a proceeding, in the likely event that privileged information is produced during discovery.

- Privilege log. Keeping a detailed privilege log will help you avoid a costly discovery dispute or waiving privilege.

- Communications training. Teach your organization proper privileged communication tactics, like designating in email that information is privileged or favoring a phone call over text.

Most in-house counsel managing litigation understand discovery obligations and the basics of how to protect attorney-client and work product privileges from disclosure in the United States. Even so, counsel should be aware of the effect of globalization on litigation and the impact cross-border discovery has on privilege. Now may be the time to consider a refresh of in-house privilege protocols, strategy, and training. New practical tools, updated techniques, and outside-counsel practices, in combination with standard operating procedures, can aid in the recognition and protection of privileged documents.

The problem: More discovery, more data, and more potential privilege disclosure risk

Even with advanced search technology, artificial intelligence, and effective information governance programs (check out the resources available from the ACC Information Governance Network), data volumes are growing — just ask your chief information officer. According to The Radicati Group’s annual Email Statistics Report, worldwide email is expected to increase about 4.4 percent annually with the average number of business email messages a user manages nearing 300 per day. There has also been an explosion of messaging apps, with roughly a third of the world’s population regularly using them to communicate. A similar scene exists in the workplace with the growing adoption of collaboration tools like Slack, Microsoft Teams, and Workplace by Facebook.

Both sides of the “v” should be concerned. The eyes of discovery have recently focused on cloud-based social media accounts. At the same time, large data holders now

face private equity-funded opposing counsel with refreshed resources to comb through documents using sophisticated artificial intelligence technology and brute force human document review. The end goal of many of those requesting parties? They want to locate evidence related to the claims in the case — with the bonus of uncovering secrets regarding other potential claims (on other products and services) that have little to do with the matter at hand. In the meantime, typical producing parties are trying to minimize the amount of data they are producing to mitigate risk and reduce cost.

Even with the limitations from the 2015 amendments to the scope of discovery permitted by Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 26(b)(1), the US litigation landscape provides more open access to an adversary’s files than other contemporary industrialized nations. Recent Third Circuit rulings in In re Generic Pharmaceuticals Pricing Antitrust Litigation went so far as to mandate inflexible keyword-based document production, stripping a producing party’s ability to review documents for relevance prior to production. Requiring the production of irrelevant documents simply because they hit on a search term directly conflicts with Rule 26(b)(1)’s limitation on discoverability to relevant documents. The Generics dragnet discovery order was so controversial that defendants petitioned the US Supreme Court and recently, the Court stayed the Generics case pending further order of the Court.

The end goal of many of those requesting parties? They want to locate evidence related to the claims in the case — with the bonus of uncovering secrets regarding other potential claims (on other products and services) that have little to do with the matter at hand.

The good news: In the United States, both attorney-client and work product privileges still maintain sacrosanct status. Basically, this means broader discovery with guardrails to protect the legal advice and the work around it. Process and procedure are critical to combat US-focused challenges — especially when choice of law is a concern.

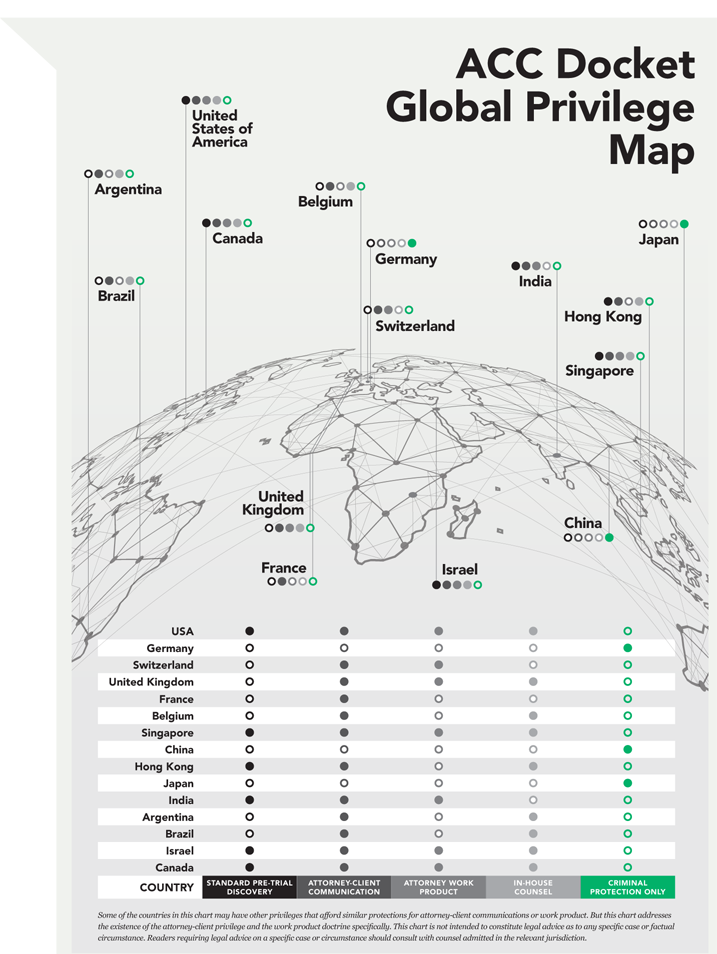

Is US privilege law applied to content created in another country? If cross-border discovery is permitted, parties must be prepared to address the question of which country’s privilege laws apply. As a matter of fundamental fairness, a requesting party should not be permitted to mix and match broad US discovery with a foreign jurisdiction’s lack of privilege protections. The reality is that strong privilege protections are not needed in a foreign jurisdiction that does not permit US-style discovery. Requesting parties should not be permitted to gerrymander the privilege laws to strip the privilege out in US litigation. Privilege is needed to protect candid attorney-client communications as an exception to the domestic general rule of broad discovery.

The Judicial Perspective

By the Honorable Elizabeth D. Laporte

During privilege disputes, judges (and special masters or discovery referees) seek to protect valid claims of privilege while also preventing parties from hiding relevant unprivileged information that is needed for fair adjudication. That is, unscrupulous parties will try to wield the privilege as a shield and then use it as a sword. At the same time, judges do not want the process of protecting privilege to be so onerous that the burden is disproportionate to the benefit, driving up the costs in time and money to the point that it frustrates the quest for justice. Indeed, Rule 1 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure requires the rules to be applied to facilitate “just, speedy and inexpensive” resolution — a difficult balancing task. Further, the parties, as well as the court, have an obligation to cooperate to achieve that goal. Prudent parties should take advantage of Federal Rule of Evidence 502(d) orders to protect against inadvertent disclosure resulting in waiver in the litigation or other lawsuits or investigations — essentially a free insurance policy.

Privilege logs are the basic tool for claiming privilege while giving the other side enough information to assess whether the claim is legitimate or to challenge it. Counsel should be sure to familiarize themselves with their court’s local rules and any standing orders of the presiding judge or requirements of any special master overseeing discovery. Adequate logs usually must be specific enough regarding the subject matter of the withheld information that, together with the standard disclosures such as authors, recipients, and dates, the basis for claiming privilege is apparent. Therefore, using only metadata may not suffice. And failure to exercise due diligence in privilege logging can result in waiver. On the other hand, most judges and masters allow grouping by category. The best practice is often to negotiate a stipulated ESI protocol with the other side(s) that includes less onerous requirements, such as logging only the top email message in a thread but including all metadata from the threat, excluding information after litigation started and communications with litigation counsel.

When disputes arise, counsel should first meet and confer to attempt to resolve them — usually a prerequisite to bringing the dispute to the court. If the parties cannot resolve the dispute, be careful to present it in a manageable way to the judge or master, who will not look kindly on a request to review hundreds of documents in camera (that is, in private). Faced with such requests, I have ordered counsel to select a small sample of documents that they view as most suspicious for in camera review. I then ruled on those and asked counsel to apply the same reasoning to the remaining documents, which typically resolves the dispute. Counsel can proactively suggest this procedure.

Counsel in cases involving international companies or transactions should try to anticipate and plan for cross-border issues that may arise from the many jurisdictions that do not allow the broad discovery afforded in the United States and therefore do not need or have the same attorneyclient and work-product protections. As I wrote in Teradata Corp. v. SAP SE, courts should guard against a mismatch of the different systems to allow unfair invasion of legitimate privileges, but the case law on this topic is not uniform and continues to evolve. Honorable Elizabeth D. Laporte She is an arbitrator, mediator, special master/referee, and neutral evaluator at JAMS San Francisco. She handles matters involving antitrust, business/commercial, civil rights, employment, environmental law, insurance, and intellectual property.

Honorable Elizabeth D. Laporte She is an arbitrator, mediator, special master/referee, and neutral evaluator at JAMS San Francisco. She handles matters involving antitrust, business/commercial, civil rights, employment, environmental law, insurance, and intellectual property. Judge Laporte is the former chief United States magistrate judge for the Northern District of California.

Five practical tips to protect privilege in a globalized litigation environment

1. For US litigation, get a Federal Rule of Evidence 502(d) or an analogous state non-waiver order

Even though it has been around for over a decade, parties are still underusing Federal Rule of Evidence 502(d), which provides that disclosure of a privileged document will not act as a waiver in the pending litigation or any other federal or state proceeding. It is inevitable that parties will inadvertently produce privileged information during high-volume electronically stored information (ESI) discovery. Rule 502(d) provides a safety net. Judges across the country urge parties to use the rule and chastise those who do not (see sidebar below).

For instance, in Brookfield Asset Management, Inc. v. AIG Financial Products Corp., the parties had entered into a Rule 502(d) agreement at the court’s urging. The defendant then produced documents with privilege redactions but where the redacted text was visible in the corresponding metadata. Pursuant to the Rule 502(d) agreement, the court granted the defendant’s request to claw back the documents, “no matter what the circumstances giving rise to their production were.” Contrast that with Ranger Construction Industries, Inc. v. Allied World National Assurance Company where the court expressed dismay that the parties did not enter into a Rule 502(d) agreement:

Sample FRE 502(d) order language

“The production of privileged or work-product protected documents, ESI or other information, whether inadvertent or otherwise, is not a waiver of the privilege or protection from discovery in this case or in any other federal proceeding.”

This ESI Protocol shall be interpreted to provide the maximum protection allowed by Federal Rule of Evidence (FRE) 502 and shall be enforceable and granted full faith and credit in all other state and federal proceedings by 28 U.S. Code § 1738. In the event of any subsequent conflict of law, the law that is most protective of privilege and work product shall apply. Nothing contained herein is intended to or shall serve to limit a party’s right to conduct a review of documents, ESI or information (including metadata) for relevance, responsiveness and/or segregation of privileged and/or protected information before production.” – In Re Taxotere MDL PTO 49 also located here.

The Court is frankly surprised that the sophisticated attorneys in this case did not enter into a written 502 claw-back agreement early on in this litigation, either separately or as part of an ESI Protocol Agreement. This Court encourages counsel in all cases involving eDiscovery to consider the benefits of jointly entering into a 502(d) claw-back agreement and/or an ESI Protocol Agreement early on in the case.

Parties that fail to get a Rule 502(d) order do so at their own peril. For instance, in Irth Solutions v. Windstream Communications LLC, the parties agreed that a Rule 502(d) order was not necessary. Instead, they agreed among themselves that an inadvertent production of privileged documents would not operate as a waiver. Inevitably, a party inadvertently produced privileged documents. The court held that the privilege was waived because the production was reckless and therefore did not satisfy the reasonableness prong of Rule 502(b).

But even with a Rule 502(d) order, producing parties should still conduct a diligent privilege review. While a Rule 502(d) order protects against the disclosure of privileged information, it can sometimes be difficult to unring the bell. A receiving party who views a privileged document from a producing party has learned information to which they are not entitled and may try to use that knowledge to structure further discovery to take advantage of the disclosure.

2. Seek an order that clarifies the handling and logging of privileged information — consider obliging counsel to “stop reading and notify”

In project management, a death march defines a project that the participants feel is destined to fail or that requires a stretch of unsustainable overwork. Welcome to privilege logging. Though time-consuming and burdensome, the privilege log is the customary means of complying with the requirement to describe withheld ESI. As one judge put it:

No doubt, the preparation of privilege logs is tedious, and electronic discovery is the bane of many lawyers’ existence. Nonetheless, as Daniel Webster said, “If he would be a great lawyer, he must first consent to become a great drudge.” Preparation of privilege logs is the type of drudgery to which lawyers must pay careful attention if they want to call themselves “great.”

Plan ahead; a deficient privilege log can result in severe consequences, including costly discovery disputes or waiver of privilege. Thus, it is crucial for counsel to properly comply with and understand their obligations. Consider agreeing to the fields that will appear in the privilege logs, perhaps even sharing a sample entry or two to reach format agreement and to set expectations.

One way to navigate the burden of privilege logging is for the parties to agree at the outset to codify an ESI protocol or protective order that guides privilege logging. For example, some ESI agreements and orders allow for:

- Categorical logging;

- Metadata-only logging;

- Logging only the top-most email messages in a thread while including metadata from all email messages in a thread; or

- Exclusions for redacted documents or communications that post-date the start of litigation.

- While Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 26(b)(5) requires parties to describe withheld documents to support the basis of privilege, it does not specify the format of the log. Rather, the Advisory Committee Notes following Rule 26 indicate that less burdensome means should be employed where appropriate:

[Rule 26] does not attempt to define for each case what information must be provided when a party asserts a claim of privilege or work product protection. Details concerning time, persons, general subject matter, etc. may be appropriate if only a few items are withheld, but may be unduly burdensome when voluminous documents are claimed to be privileged or protected, particularly if the items can be described by categories.

Thus, the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure expressly provides for various alternatives companies should consider to reduce the privilege log burden.

The parties may implement all of these considerations in an early protective order that clearly delineates the handling of privileged information. Also consider the choice of professional responsibility law in larger matters with counsel from multiple jurisdictions. As a producing or receiving party, understand the obligations of a receiving party handling privileged information with an inadvertent production. For example, unlike the ABA Model Rule, New Jersey’s version of Rule of Professional Conduct 4.4 requires the lawyer to stop reading the document when the lawyer realizes that it (or its accompanying embedded data) was inadvertently sent and to notify the producing party of the inadvertent production. The parties may create their own obligation, including mirroring New Jersey’s requirements, in the ESI protocol to prevent the use of inadvertently produced privileged documents.

3. Understand choice-of-law risks with cross-border ESI

A recent case where a requesting party attempted to mix and match US discovery law and German privilege law provides a helpful analysis for parties navigating cross-border discovery issues. In Teradata Corp. v. SAP SE, the plaintiffs moved to compel audit-related documents identified on the defendant’s privilege log, arguing that German privilege law, which does not recognize a privilege for in-house counsel, governed. In support of this argument, the plaintiffs stated that the audit took place in Germany, was directed by German in-house counsel, involved interviews of Germany-based employees, focused on conduct that largely took place in Germany, and was provided only to in-house counsel in Germany.

Also consider the choice of professional responsibility law in larger matters with counsel from multiple jurisdictions.

But the court held that US privilege law applied to the audit-related documents because the focus of the audit was on the relationship between the defendant and the plaintiffs, which demonstrated that the audit “touches base” with the United States. The court further noted that the plaintiffs had failed to meet their “burden to show that the audit had nothing more than an incidental connection with the United States or that Germany has the predominant or most compelling interest in the audit.”

The court said that “when any large, multinational organization conducts audits, to make them efficient and cost-effective, they often will need to span overlapping jurisdictions,” but “[t]hat reality should not lead to the fundamentally illogical and potentially very unfair result of nullifying the US attorney-client privilege due to the mixing and (mis)matching the law of different jurisdictions.” The court further stated, “It makes little sense that the lack of a privilege not needed in a foreign jurisdiction because it lacks US-style discovery leads to the stripping of the privilege in US litigation, where it is needed to protect candid attorney-client communication as an exception to the domestic general rule of broad discovery.” The court concluded that the practical reality — as opposed to the hypothetical possibility — is that even if German privilege law were to apply in this case, it would be unlikely that a court sitting in Germany would compel disclosure of the documents at issue.

4. Plan witness interviews carefully — even the privilege of outside-counsel interview notes and memos may be challenged

In a cross-border investigation and tag-along litigation, attorney work papers should clearly identify that the client is contemplating litigation and the purpose of the work is driven by that potential litigation risk. These efforts will assist counsel in protecting notes generated from the inquiry. While US attorney-client privilege and work product protections would prevent discovery of attorney notes, in the United Kingdom, the content of internal employee interviews is not necessarily protected. In R(AL) v SFO, the High Court stated “The law as it stands today is settled. Privilege does not apply to first interview notes.” The court reasoned that the first interviews were not related to litigation and were more aligned with the business decision to self-report.

The makeup of the interview teams may trigger other privilege considerations. If employee non-attorneys are required to attend the interviews or prepare materials, document that the non-attorneys are working at the direction of outside counsel.

The UK Court of Appeal extended a previously more limited legal advice privilege to protected communications to a broader range of employees beyond the board in Serious Fraud Office v Eurasian Natural Resources Corporation.

The court ruled as follows:

if a multinational corporation cannot ask its lawyers to obtain the information it needs to advise that corporation from the corporation’s employees with relevant first-hand knowledge under the protection of legal advice privilege, that corporation will be in a less advantageous position than a smaller entity seeking such advice. In our view, at least, whatever the rule is, it should be equally applicable to all clients, whatever their size or reach.

While the Court’s ruling provides good movement in the direction to protect privilege in larger organizations where counsel may not be acting at the direction of the board, counsel should be mindful to limit communications.

5. Consider careful communications training and write-right programs

In any country, the best way to maintain privilege is to communicate properly in each of the organization’s jurisdictions. Why write an email when a phone call might be better? If it was never created, there is no risk of waiver.

Also, simple things like advising business employees how to properly designate communications as privileged in the text of email messages:

PRIVILEGED & CONFIDENTIAL ATTORNEY WORK PRODUCT PREPARED AT THE DIRECTION OF COUNSEL ATTORNEY-CLIENT COMMUNICATION

Blatant designations will help trigger privilege filters deployed during document production. Also, showing clients and business employees a sample of notorious smoking-gun email messages (available widely on the internet) from historic litigation may increase compliance with careful communications programs — some clients integrate email-usage training into annual compliance programs for the workforce. Write-right training programs are easy to create and often a good value-add training request for outside counsel.

Conclusion

Applying these practical tips can help mitigate concerns regarding disclosure of privileged information in both domestic and cross-border litigations. With data volumes growing exponentially and discovery becoming increasingly globalized, planning ahead is a necessity. By implementing these practices and techniques, in-house counsel will fortify the protections afforded by the attorney-client and work product privileges.

References

MDL No. 2724 (E.D. Pa.)

See Garden v. Continental Cas. Co., No. 3:13 CV 1918-JBA, 2016 WL 155002, at *2–*3 (D. Conn. Jan. 13, 2016) (rejecting a similar proposal as “simply untenable” and stating, “As every law school student and law school graduate knows, when performing a computer search on WESTLAW and/or LEXIS, not every case responsive to a search command will prove to be relevant to the legal issues for which the research was performed. Searching tens of thousands, and hundreds of thousands, of electronic documents is no different.”).

No. 09 Civ. 8285, 2013 WL 142503, at *1 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 7, 2013).

No. 17-81226-CIV, 2019 WL 436555, at *2 n.2 (S.D. Fla. Feb. 5, 2019).

No. 2:16-cv-219, 2017 WL 3276021, at *1 (S.D. Ohio Aug. 2, 2017).

Id. at *2.

Id. at *14

LaVeglia v. TD Bank, No. 2:19-cv-01917, 2020 WL 127745 (E.D. Pa. Jan. 10, 2020).

See, e.g., id. (requiring the party to re-create their privilege log properly).

Fed. R. Civ. P. 26 advisory committee’s note (1993); see also, e.g., S.E.C. v. Thrasher, No. 92 CIV. 6987,1996 WL 125661, at *1 (S.D.N.Y. May 1, 1995) (detailed privilege logs with information regarding each document are not required, including where “(a) a document-by-document listing would be unduly burdensome and (b) the additional information to be gleaned from a more detailed log would be of no material benefit to the discovering party in assessing whether the privilege claim is well grounded”).

No. 3:18-cv-03670 (N.D. Cal. Sept. 9, 2019) (Laporte, J.).

[2018] EWHC 856 at ¶ 105 (Admin).

Id. at ¶ 111.

[2017] EWHC 1017 at ¶ 126 (QB).